"My Prison-Cure in America", Chapter 2

Adapted from Annemarie Schwarzenbach, by Cleo Varra

CW: Involuntary hospitalization; restraint & seclusion; suicidality

Read previous: #1. A Doctor Came Into My Bedroom, And I Woke Up

----------------------------

Bellevue Hospital, New York City-- 1941

For the next few days I was in semi-darkness, stretched out on a bed.

I waited and waited and the agony didn't get any less, and I sometimes wondered why I didn't die.

When they untied my hands, I put them to down to rest upon my thighs.

***

The guard beside my bed, who had sometimes helped me smoke, slipped the cigarette between my fingers, and I found it oddly liberating, to be able to raise my hand, and bring it to my own lips.

Soon, someone came and took the cigarette away. They asked me: —Where did you get that from?

I opened my eyes, and nodded to the open pack, lying on a table by the wall.

Then I noticed that my feet were tied to the bed with leather straps, and spread apart; but I said nothing.

***

I saw the orderlies nod at each other; then, while they were busy retying my hands as well, I saw in the doorway the face of the man who had been sitting next to me, guarding me.

He was a very young man, maybe sixteen at most. The guard’s smock billowed like a white dress, under a belt around his long, childish hips.

He had leaned his head against the doorpost, his pink lips were parted, and he looked at me silently and intently,— and waited, almost thoughtfully, ready to smile.

I understood that he wanted to ask me not to reveal who had given out the cigarette. I parted my lips wordlessly, too, and the boy and I exchanged a smile.

*******

"Mrs. Henrietta Hoffman, the matron of the [...] institution said that handcuffing had a good effect. Ruth Carter, the girl whose story of suffering at the institution started [this] investigation, liked the handcuffs and would not take them off, because she liked the soothing effects, according to Mrs. Hoffman."

-- New York Times. "Denies Brutality at Reformatory".

Nov. 22, 1919.

***

Later I would walk freely through the halls and corridors of the hospital.

Before that, when I was still tied to my bed, the doctor came once.

He only came as far as the door, and he asked in a friendly way: “Feeling calmer?”

I didn't answer.

I looked at this man, who, perhaps for the sake of convenience, had brought me here and delivered me up to a nameless force.

But my thoughts rushed past him, and startled me.

—“Now I know what it is to kill a person”, I thought.—

“It's nothing. It's just a gesture of the hand.”

That's what I thought, while the walls of my cell still filled me with panic.

***

I remembered that I’d wanted to ask the doctor a series of questions:

Whether I was under arrest, or just a patient;

In which hospital I was;

Whom I could call;

Whether it might not be possible to remove these unnecessary and very painful shackles.

***

"W.G. Barrett, Chairman of the Board of Managers [said] "I would not approve of handcuffing... except where a hysterical girl cannot be held except by four or five guards. ...So in extreme cases, I approve of it."

-- New York Times. "Denies Brutality at Reformatory".

Nov. 22, 1919.

***

Rather die, I thought; but my thoughts became confused.

It would be better to die than to hopelessly scan these walls— rather sink into the unknown than linger one more second upon this man whose eyes-- bored, superior, and cold-- now were passing over me.

While time ran out, and I held my breath, it seemed to me briefly as if my life were over.

— The consuming hatred which I felt for this man had sucked up the last of my strength, as if in one last, deep drag.... And this, finally, would be the end of me.

***

— The doctor went on talking:

“Your fever has already gone down, soon they will be able to transfer you to the hall next door…. You will feel better there.”

But his eyes flickered uncertainly, and he fell silent.

I knew that I couldn't answer anything.

I was tied, and it was an exhausting effort even to raise my head.

In any case, it seemed like he would be unable to stand my gaze for much longer.

It seemed to me as if his eyes were beginning to fill with warmth, becoming uncertain; and his light forehead had reddened, as if from shame.

He turned as if to summon a nurse, to give an order to a guard. But they were all gone.

I wanted to lower my eyes, but I couldn't.

I heard myself say in a low, flat, almost unfamiliar voice: “Would you please leave me alone.”

At the same time, I felt such pain inside me that I thought I would faint.

The doctor didn't say a word, and was obviously happy to be able to walk away....

I was then left lying on my bed for a long time.

"The scientific study of the psychopathology of sexual life necessarily deals with the miseries of man and the dark sides of his existence, the shadow of which contorts the sublime image of the deity into horrid caricatures, and leads astray aestheticism and morality. It is the sad privilege of medicine, and especially that of psychiatry, to ever witness the weaknesses of human nature and the reverse side of life."

-- Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis (pg. 9).

***

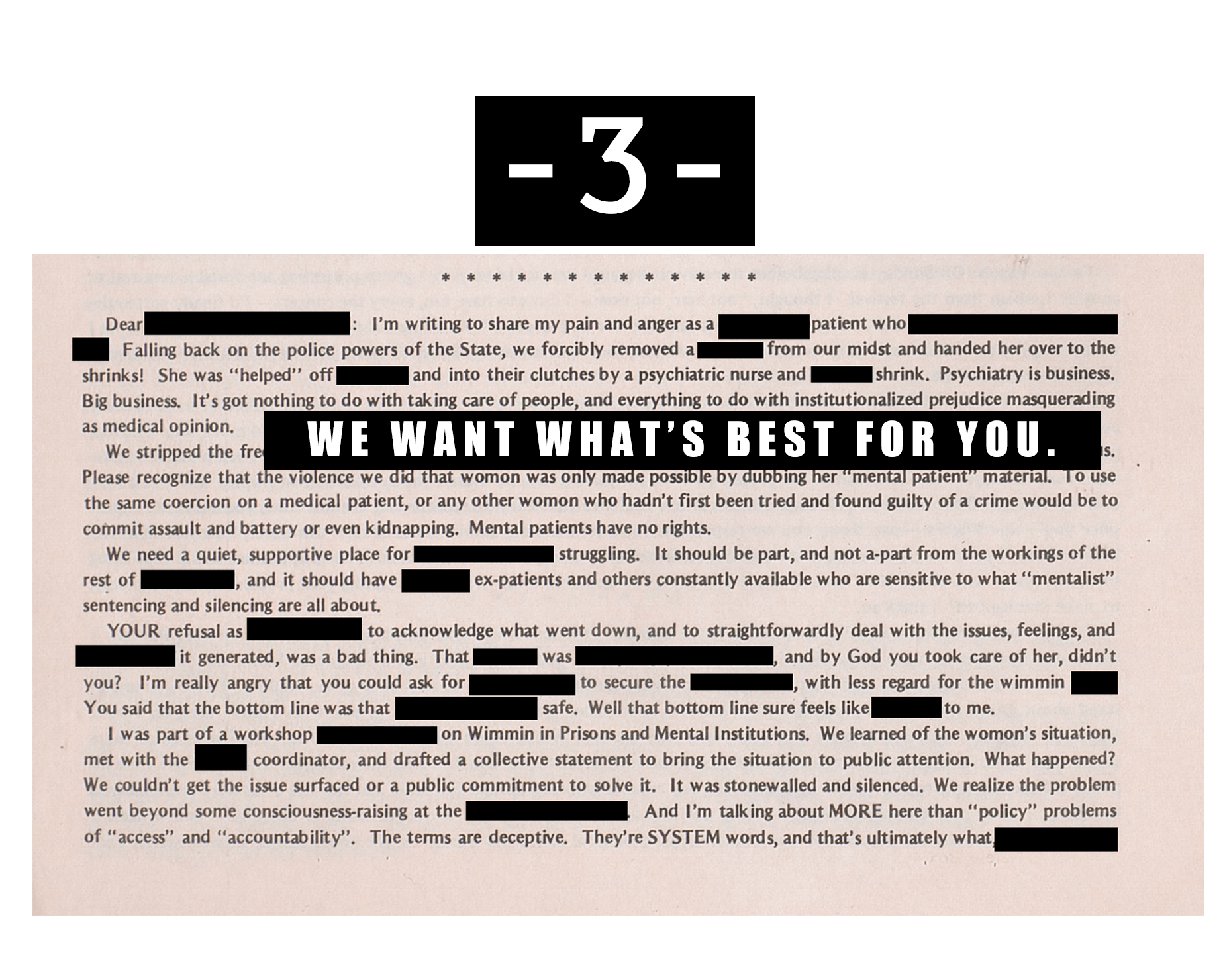

Next: #3. We Want What's Best For You