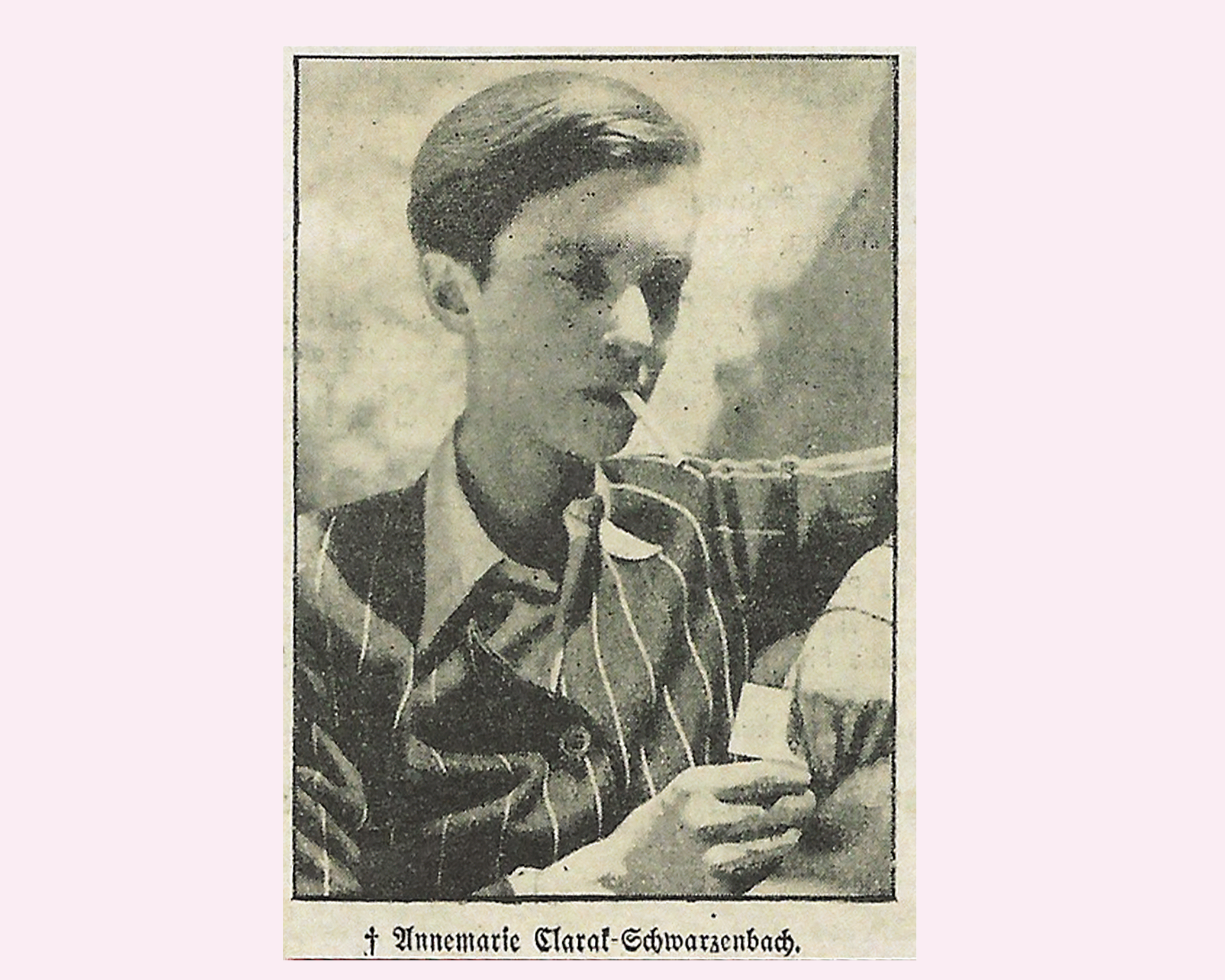

"The Happy Valley" ch. 4

By Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Abridged and translated by Cleo Varra

Previous: "The Happy Valley" ch. 3

It is becoming increasingly difficult to remember.

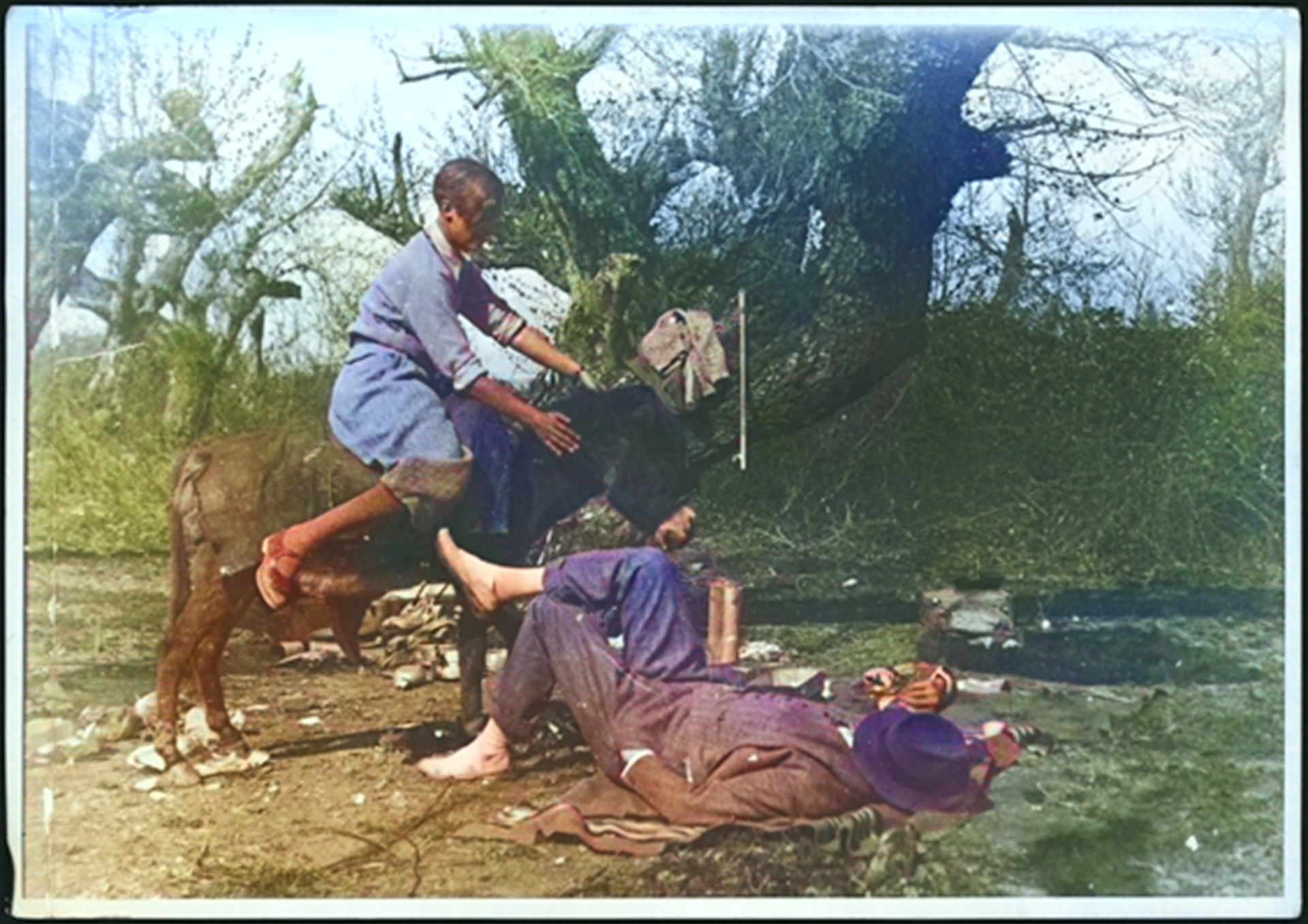

I used to keep these memories at bay— used to, until yesterday!— I had banished them, I wanted to banish myself, no exile was lonely enough for me. -A tuft of grass brings back a hundred memories, warm hay is a world of familiarity. At home, meadows bordered our garden, in the summer you could hear the mowers early in the morning and would throw open the shutters. Early morning rides, turning off the road, the hooves of the galloping horses sounding muffled on the track of the riding arena. And alpine meadows, on the Rigi, on the Mythen, in the Engadin! The farmers came over the steep slopes, the hoods of their white shirts pulled over their heads, their necks bent under huge bales of hay, which their strong arms held in balance. - Picking raspberries for lunch, the smell of melons, huge pans in the kitchen full of freshly preserved cherries, blackberries, apricots, and what else! - Memories, familiarities, consolations - a dry tuft of grass in the desert is too much! - I was right to banish, forget, erase the traces. Can't one avoid the straits, the arms, fjords, waterways, the Swedish archipelagos, the putrid canals of Venice that one finds again in Amsterdam, in Danzig? I wanted to discover foreign ports, billowing with rust-brown sails - a forest of masts, sirens, fishing boats, wine bars, dives. I spent an evening on the hills of Cyprus and looked down on the port - what was it called? - Out on the blue water lay an Italian steamer, flag hoisted, bridges dazzling white. At its side a low barge, the deck crammed full of mules that were loaded onto the steamer. They were strapped around their waists, a crane hoisted them up. I saw their helpless hooves dangling.

Then I saw a flotilla of barges break away from the harbor, they covered the whole bay, their evening-red sails billowing, they overtook each other, shot out, lay to the side, circled the steamer - tanned boys climbed the railing, the white-bearded old men in turbans handed them baskets filled with shells, glass beads, embroidery and heavy grapes... Behind us the city, the white houses, the busy streets, the antique dealers, the department stores, the alleys, the courtyards in the dark, the mosques, the baths.

And one day on the lonely shore of Byblos.

In the warm salt waters, the foam crests, nestled in the warm sand. Beyond the rocks, brown farmland - to the left, the grace of Greek columns. The old city of Byblos rocked on cliffs above the Mediterranean! It bridged Egypt and Greece! - In my dreams, church bells rang: in the next village I found crucifixes and images of saints.

It was January 19th.

Of what year?

***

In Beirut I said goodbye to my friend Fred.

On the last day we went to all the antique shops to buy him a souvenir. He took a yellow silk coat, a blade from Damascus, a goat's hair blanket and a small lion's head made of white alabaster.

I had been haggling over this piece for a long time and my heart was set on it. Broad cat's forehead, open jaw, narrow eyes, temples, neck: everything perfect - it didn't matter that one ear was damaged, leaving a crack across the transparent skull. - In the evening, at the hotel, Fred packed up all the souvenirs. Then we went to the harbor, Mahmut carried the luggage. We drank raki in a bar. "For the last time," said Fred. Milky white drink, sweet aniseed flavor - we had drunk it together in Ankara. In Kaiserie, in Konya, Aleppo, Rihanie, Baalbek. And never again. Fred traveled to Trieste, Milan, Zurich, Berlin.

"Say hello to friends!" - We would no longer speak of Zurich and Berlin, of friends, of old habits. - At the last moment, the customs officials wanted to keep Fred back because they found a revolver in his handbag. I had to talk to the inspector, whom they had woken up, drink coffee with him and appease him. Mahmut scuffled with the guards and was locked up. Fred was led in a hurry to the motorboat, which then pushed off from the shore and disappeared into the darkness.

The steamer's siren wailed outside.

Fred was gone, the inspector invited me for a second cup of coffee. He was wearing slippers and a French uniform.

I asked him to release Mahmut. It took a long time. The ship had long since left the harbor bay when Mahmut and I walked back through the empty streets to the Hotel Metropole. Fred was probably already asleep in a white cabin - with him the little lion's head. I had sent the souvenirs away. I wanted my luggage to become lighter and lighter. No objects, no pictures, no books. No names. And no roof over my head…

***

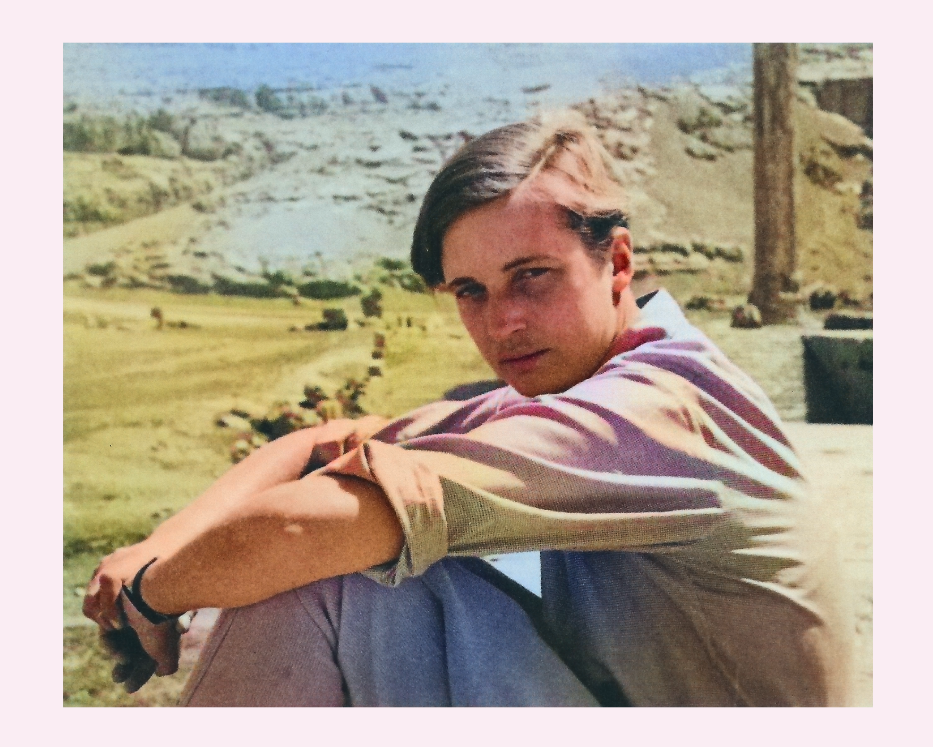

I wanted to be unburdened: hadn’t I such a long journey ahead of me? - And no destination! - These cities were not built for me, the towers without greeting, the prayers in foreign tongues - no house opened to welcome me, no lamp was over the courtyard gate to show me the way home.

I met people, they became friends - never companions. Ah, what separations, what farewells! Before each new departure I was torn apart by fear: setting off alone…. And yet: just as one hesitates on the border between night and day, just before dawn, and says to oneself "It will never be day again", while violet light is gliding over the horizon, announcing the radiant rebirth - so the first hour of departure brought ample consolation. My heart became light, empty, sober, receptive. Fear fell away from me. In front of me was a white road, a desert track, a mountain path, I do not know where they end - thank God! - For a second I sense liberation… and the city I have just turned my back on lies in ruins. - Did I really feel safe within its walls? - Nestled in the gardens of friends, sitting with them by the fire, sharing the light of the lamp with them in the evening, and their meals, their habits, their joys? Did I become one of them, did their dogs know my whistle and recognize my step when I turned into the street, opened the garden gate, climbed the stairs to the room that had already become my room? - Me: a guest, a stranger, an adventurer, what else - curious, thirsty for knowledge, impatient, on the move -, alone. They forgot what I was.

They took me in. And eager to find out how they live, I lived with them.

What a temptation: to live with them. With you. To live together. - The steppe no longer burns, the night is without flames. The glaciers are far away. The sun no longer rises over the desert. The desert is unborn land. The sea has parted: only the shipping routes remain. In the morning roosters crow. - For the third time? - and you shake off the blankets:

It's time.

***

"To work! - Friends, comrades, to work!" - The call delighted me. - "Comrades!" - they meant me too. They didn't ask me where I came from. I didn't need any origin. I had strong arms, and my heart was ready. What had I wasted my time on until now? - Lost, homeless, idler on every road, exposed to the wind, the cold, hunger. Always alone, pushing forward to the edge of abysses, in which liquid rock still boiled, the unadulterated heart of the earth. What was I doing there? - Days of staggering exhaustion- and sleep that did not refresh me -, wandering flames on the horizon. Nevertheless, at dawn, you would pull yourself together again, your heart would throw itself at unknown consolations. And find itself again in the desert, under the terribly empty sky…..

It’s gone, forgotten. - I am tired, I am among you, I am staying. - A coincidence brought me to Ankara. How long did I stay? - I was given a horse to ride, a golden chestnut, a young mare.

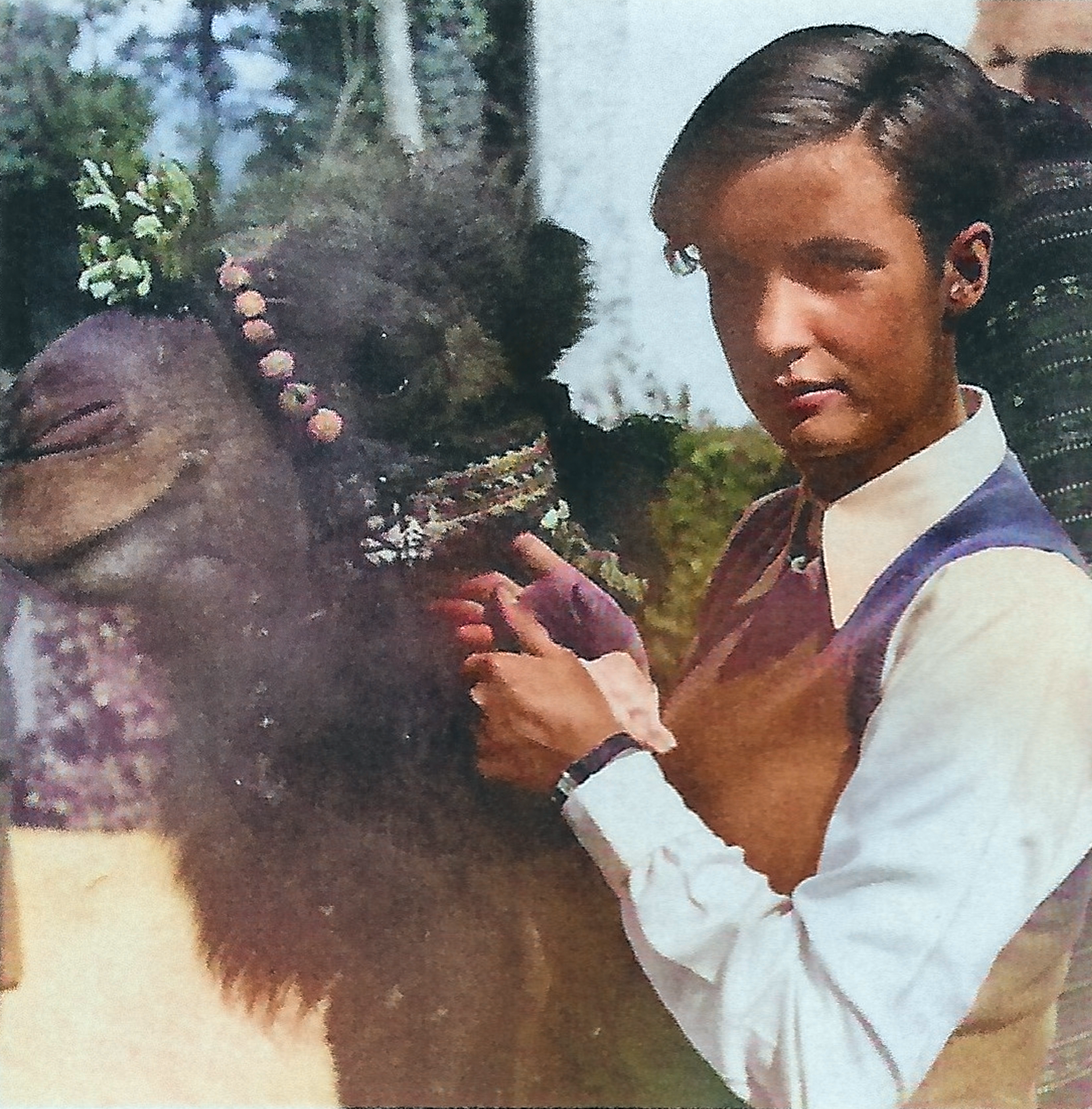

Her name was Büske and she was full of grace.

She greeted me with a neigh when I entered the stable in the morning. A Turkish soldier put the saddle on her and led her into the riding arena. "She still needs a lot of work," said the Hungarian trainer - "but she has a chance of winning the club race in three months." - Work every morning, and a gentle gallop on the steppe floor, which muffled the sound of the hooves. Afterwards, we chatted in the bar, like professional people: emancipated young Turkish women in ill-fitting riding suits, officers, foreign diplomats, trainers, grooms. - But I did not wait for the race. I left Büske in strangers' hands. -

Wouldn't it have been possible to live in Ankara? - I knew all the streets, clubs, shops. I knew how to stop the bus that took me to Yenishir. Only a few steps to the small, white house where I lived. I had long since stopped climbing up the castle hill in the evenings and looking out over the steppe. I lived in the city, I had new habits, the days were full. And it was the beginning of winter— the Kurds on the outskirts of Ankara were freezing in their huts. And the comfort of warm rooms, in the lamplight - in the kitchen next door, the clattering of plates, the smell of apple strudel. My friends were Austrians.

Why didn't I stay in Ankara? - Now, when I think back, I hear the steppe wind again. I walk along the road again, which - like many of the new roads there - led nowhere and disappeared in the grass of the wilderness. I see the velvety hills again in the evening light: violet, red, midnight blue, flaming yellow stripes divide the sky. And I hear again the monotonous, groaning cries of the ox carts, which have been digging tracks into the earth of Anatolia for a thousand years on their heavy wooden disc wheels. People call them "nightingales". Their song rolls across the steppe again. I hear it again. Follow the tracks? - The wandering nomad fires? - A cold glow lies on the frozen plains, the little greyhounds bark in the villages, the huts are locked, smoke billows through the clay walls. Cold in Kaiserie, cold in Konya: there must be milder regions beyond the Taurus.

***

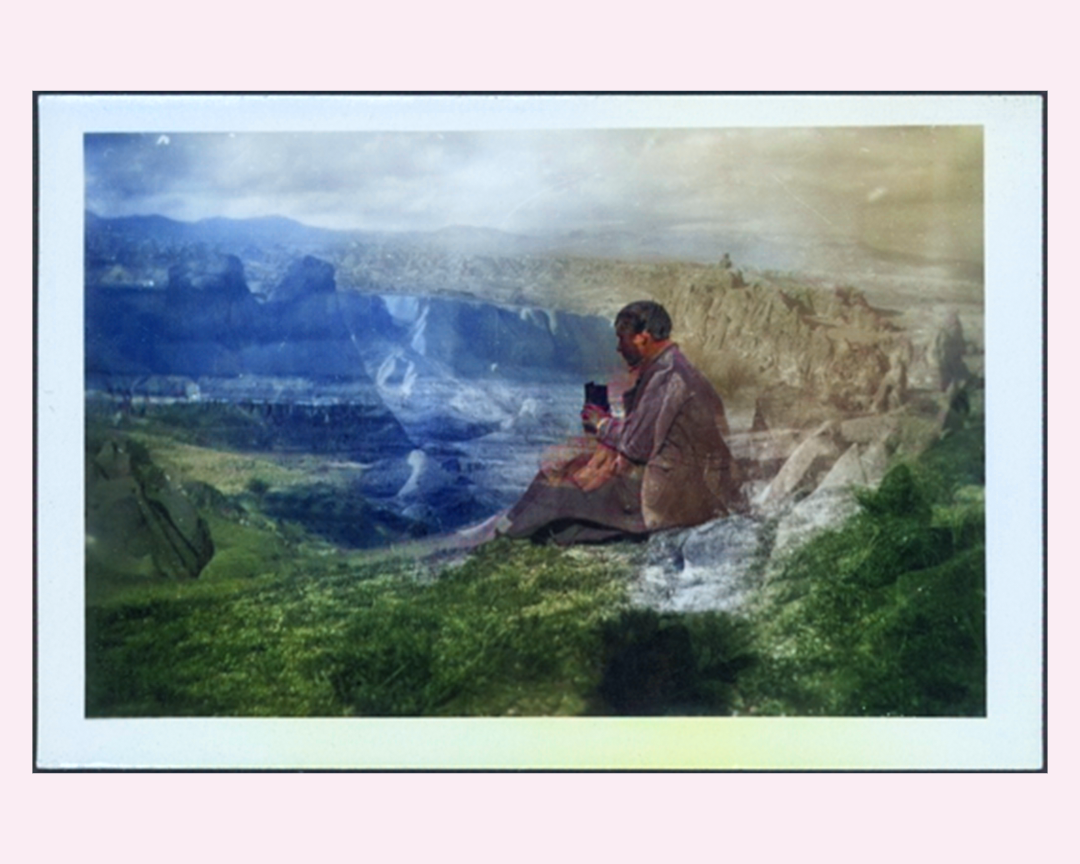

So one day I came to Rihanie, a Syrian village one hour from Aleppo. Didn't I want to be an excavator? - To practice a trade! - The house of the American expedition was on a hill, you could overlook the Afrin River and the wide plain with its dark hills of ruins.

Our hill was called Çatalhöyük. There was work to do, everyone's hands were full! - Remove layers of earth dating back centuries, Arab, Byzantine, Hellenistic, Assyrian - remains of walls, graves, house quarters, temples - clay jugs and urns, seals and spindle weights, foundation nails, votive animals, small deities, skeletons, shards. We brought a Ford car full of shards home in the evening! - Get excited, don't waste any time. Rainstorms washed away the graves, destroyed the plan of the houses. Anguish of the architect. The director wrote a report to Chicago, whiskey bottle beside him. The Egyptian cook's meals were sumptuous. My friend Bob and I drove to Alexandrette and fetched a Christmas tree. At six o'clock every evening we stopped working and drank raki by the big fire. Well-deserved rest, well-deserved sleep in our rooms where the petrol stoves were burning. Early in the morning Mohammed brought hot tea to wake us up; you could hear him walking from door to door on the stone tiles of the courtyard. And then everyone was on their feet, in high Russian boots, woolen shirts, and gathered in the dining room. Coffee, bananas, oat flakes, eggs, orange marmalade, and more coffee. In the courtyard, the truck's engine started. Mac looked at his watch, put a pack of cigarettes in his breast pocket. On the road to Çatalhöyük we overtook the Arab workers: two hundred of them. Women and boys as basket carriers...

Winter in Rihanie. I have become an excavator. I belong to the guild. Bob and I are sent to Beirut to hand over a cuneiform inscription that we cannot decipher to the American university. We drive with Hussein, the Turkish driver. On the wooden door of our "Ford station car" the name of our expedition is written in white letters. We drive to Homs, to Baalbek, Damascus. We drive through Lebanon and back to Aleppo, along the Mediterranean coast. After ten days we return to Rihanie. The usual work begins again. Winter rain in Rihanie… And the farmers in their fields. Peter's fish catch. We read coins under the microscope. We know chemical processes to check the origin of the clay. Next year we will discover new ruins in an airplane.

We will attach the camera to a balloon and photograph the history of peoples. Our methods are becoming more and more advanced. We will have a crane to carry away the earth - we will no longer pay the basket-carrying boys. In Rihanie the latest magazines are on display. The latest discoveries. The workers are working non-stop. Everyone in their place. And on time! - Triumph of technology!

Don't let yourself be put off. The work!… The work of man...

The digging continued in Rihanie, we were now at the Hittite layers, and a mild spring was setting in. The plain turned green, and the sight of the dark mounds of broken glass, long grown familiar, could not frighten us.

I had gotten used to saying "we," loudly and clearly. I never asked myself whether I loved the expedition house, whether I loved my comrades, whether I loved the work I was doing. We had forgotten that chance had brought me to Rihanie.

It was hard for me to say goodbye.

***

I could have stayed in Rihanie. I had also been offered the opportunity to go to Ras Shamra, to that wonderfully varied and productive Syrian excavation site where Mr. Schaeffer has recently discovered one of the earliest, perhaps the first, alphabet.

And at least six languages were spoken in that city, students from all nations filled its libraries, traders from all countries exchanged their goods -you found all different styles, cults, divinities, priests from Egypt, astronomers from Ur and Babylon, vases from Crete and Cyprus. In Ras Shamra I could have taken part in passionate research into the beginnings of history, into the migrations and first developments of humanity. The earth itself as the keeper of its secrets! - The hill that one penetrates carefully so as not to destroy a single cell, like a scalpel into the tissue of the skin - this dark, evenly smoothed hill is not of natural origin, its layers are not geological deposits -, in a gentle depression one thinks one has discovered the site of the former city gate - and where in a clearly rounded elevation the forces seem to gather and increase, where the surface is stretched to the point of bursting like the muscular hump of a zebu, there one suspects a temple, a citadel and a royal palace - the power of government, the terror of justice, divine orders and human statutes originated from that center which is still visible today and which dominated the lives of the inhabitants right up to the last bumps of the hill, barely noticeable undulations in the ground, the unstable outskirts of the old city.

To find your way back to the soil of Syria! - The church and frescoes of the synagogue of Dura-Europos are still easy to decipher, the temples of Mithras, the barracks of the Roman legionaries, the ramparts conquered by the Persians with torches and missiles, between whose walls one finds the skeletons of soldiers suffocated by smoke, bent over.

But the altars of Petra! The mysterious city in Transjordan, the "pink city" whose camel caravans were so large that they resembled marching armies - the square stone of Dushara, the Nabataean sun god - and the round temple - one must go back to the Bronze Age, to Yemen in Arabia to get closer to its origins...

What opportunities did I turn down when I left Rihanie? What satisfactions did I give up? - Daily bread, daily work, daily increasing knowledge, a form of life in constant contact, in constant exchange with the expressions of humanity's life: had I not been carried by the stream of their destinies? Had I not been able to descend through the layers of centuries, layers of baked and unbaked clay, of pottery shards, demolished houses, fallen temples, graves transformed back into earth, down through the long-forgotten festivals, the forgotten church services, the celebrated and forgotten triumphs, pillages, earthquakes and resurrections - down to the deepest wells?

I saw us bent over the skulls of our hill, a happy guild. We became blind over the thousand spindle weights that we counted, weighed, marked and gave a catalog number - the coins that we deciphered under the microscope, the shards that we diligently put together like children do a puzzle.

"Everyone can only do his own thing, contribute a tiny part, advance just a foot..."

- On what path? To what knowledge? To what goal? -

***

One of the tried and tested methods used by mental hospitals is to prescribe a precise daily schedule for their patients, which keeps the patients occupied, distracts them and prevents them from having idle hours. - Filled with reading, playing cards, a midday rest, a walk, arts and crafts, the day passes quickly and gives the patient the satisfaction of having spent it in a normal way. - In fact, healthy people, normal everyday people, do not live much differently. Whether they are workers or astronomers who occupy themselves with counting the stars or tax officials: are they not all frightened by the encounter with the sky? -

The mental sanatoriums of Europe are overcrowded. The soldiers are armed. The youth are disciplined. The machines are at work. Progress is on the way. - And entire nations are gripped by psychoses. Individuals are cured with "work therapy" and led back to normal life. Normal life... how deep do its roots still reach? From what sources does it feed?

I am lying on the beach in Byblos again and listening to the sound of a Christian bell.

And it is, once again, a greeting from there!

- Should I admit that I am homesick?

Missionaries, monks, priests, descendants of the Crusaders - Syria is full of them. In Beirut alone there must be a dozen Christian bishops. One for the Armenians who are perishing in their refugee barracks made of cardboard and sheet metal behind barbed wire. One for the Nestorians, one for the Maronites, another for the Alaouites, whose blond children have Frankish blood in their veins. The mass is said in Latin, but also in Greek, Armenian, Syriac. Who still understands Syriac? - It is related to Aramaic, the language of Christ…

The monks drink Syrian wine, they follow the rules of the order and observe celibacy. They lead a life of poverty and chastity in their monasteries on the gentle slopes of Lebanon. And they are happy! - Thirty years in this country, well-liked. They consecrate new chapels. They baptize. They teach in their schools. They also participate in science and research. They compete with the archaeologists. Happy life, happy life - far from the battlefields, far from profane scenes.

I too have escaped battles, I have luckily escaped all dangers, I have found work, a peaceful existence, happiness will come. I will earn it. And I will have the right to a homeland.

But I am homesick...

A barge has left me on the beach of Byblos - a barge with torn sails. Now it is rocking on the water, the calm waves are rocking it gently, I see it, a dark hull, stripped masts, a wreck, silhouetted against a flaming evening sky - towards the west.

But there are other ships, bigger, faster, with billowing sails, with flags, with white bridges, with luxury cabins, with smoking chimneys, pounding engines, pilots, captains, timetables. In Beirut, in the travel agencies, they will tell me the departure times and issue a ticket in my name. Legally, with proper documents, issued in my name, I will land in Europe with all of my papers. In Trieste. In Athens. In Marseille. - I only have to decide. - I only had to decide to stay in Rihanie - they would have made it easy for me. A year in our expedition house, in front of the fire. Looking out over the hazy Orontes plain, over the land of Syria, to the most distant ruined hills, to a wonderfully mild horizon. Thirty years on the Syrian tells, I would put down roots! -

But it was too late.

The light of a new morning woke me, and the fanfares of departure made the earth tremble. The window panes rattled, outside fog rolled over the banks of the Afrin, the plain was shrouded, only the dark hills of ruins protruded like the heads of sleeping sea lions. Oh, it was a good life, in a blessed country... Why do I now feel like a coward, deserter, deceiver? - Me, who still has to confess my homesickness for familiar shores, hills, church towers - me, who asks for entry at strangers' doors - me, a guest in the lamplight!

What will become of me? -

Will I regret it one day? And not be able to turn back?

Will I not be able to find my way home one day?

Too late! - My God, I will regret it too late…

*****

Next: "The Happy Valley" ch. 5