"The Happy Valley", ch. 3

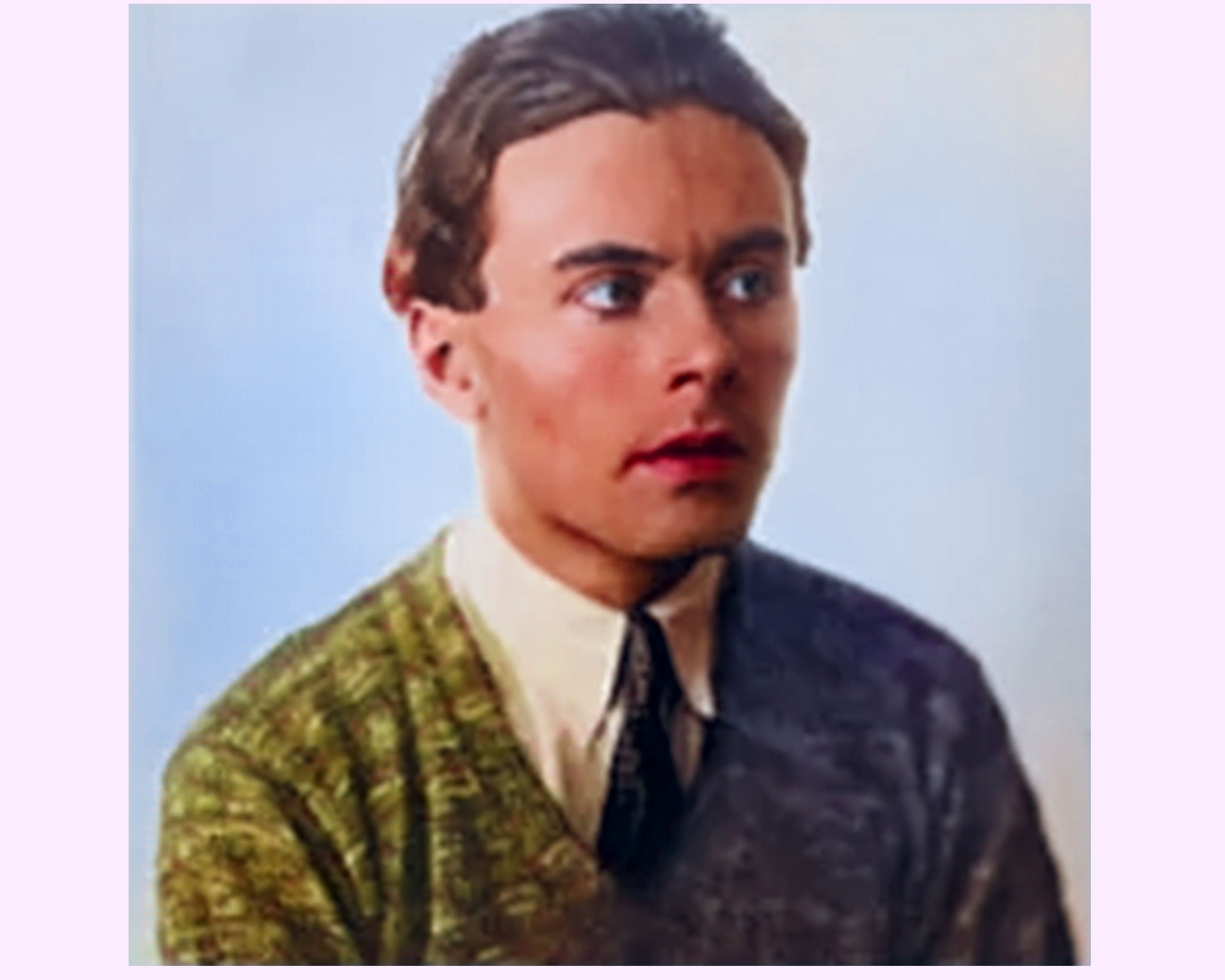

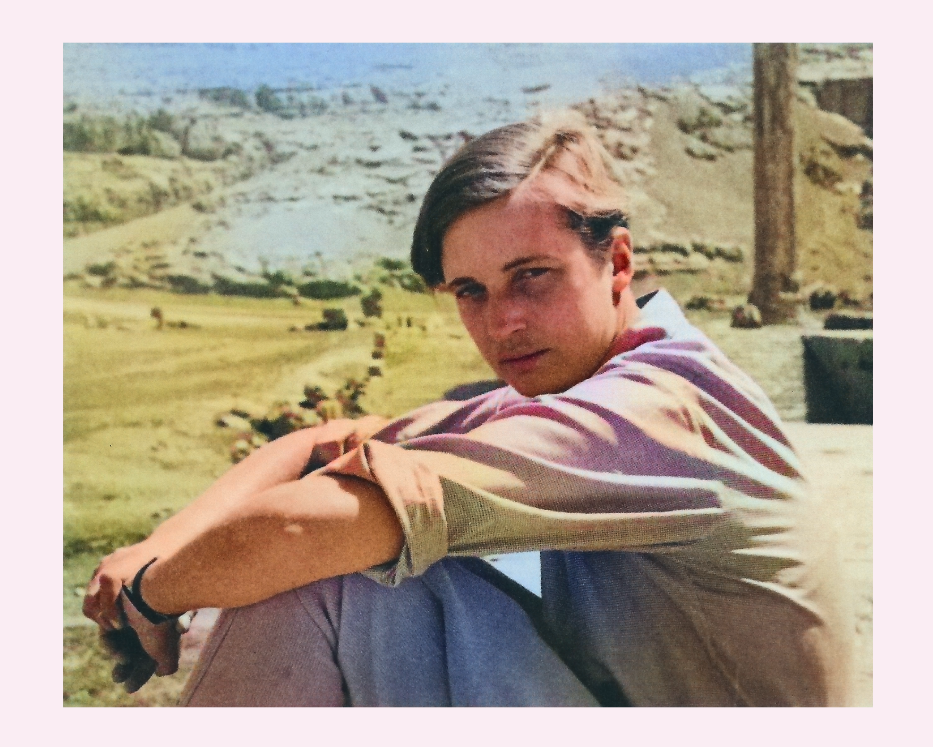

By Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Translated and abridged by Cleo Varra

Previous: "The Happy Valley" ch. 2

... but every morning when I leave my tent I am amazed by the born-again beauty of this valley.

It is still dusk, the night lamp has barely gone out, the world lies in a light high-altitude sleep. No wind stirs. The rock-crowned heads of the mountains touch the sky. The animals are resting, the birds have fallen from the clouds, the Lahr River, a wide-spread moon stream at night, companion of the Milky Way, is a young, murmuring mountain stream.

Everything is still without color, the meadows are stripped and fresh with dew, the slopes are dull basalt, their stony edges are browbands without shine, on the other bank the horses are dreaming, gray monuments. At this altitude the little chaikhana has become cold overnight. With my bare feet in the grass, coolness touches me, sleep and the warmth of dreams slip from my shoulders like a burdensome cloak. I am unharmed, light, free - no pain touches me. The Damavand is without substance, a vision of primeval times. Majestic innocence of this land! - The light is already streaking through the immeasurably tall sky— no stars, no clocks, no incense. Then the vault trembles as if under the sound of a gong. It breaks - and light rushes into the gaping crack, reaches the most distant mountains, shoots out between the rocky peaks, throws itself into the ravines -, golden brown it streams down the slopes, it travels over the rocks to the valley. The shadows cool like lava, the hills shine like the warm fur of water buffaloes, the light runs through all the valleys like a herd of gazelles. Look up! The birds have found their wings again! The ibexes cross the stones of the slopes! Camels stride majestically through the wilderness, lowering their long necks over the narrow ledge of rock to pluck tufts of grass, their humps sway, they rub their lean flanks against each other, they are gigantic, soon they will lose their balance and fall clumsily through the sky onto our tents. Warmth pours into the valley, the gravel banks are white ivory between the green of the pastures. What astonishing richness! What wonderful activity!

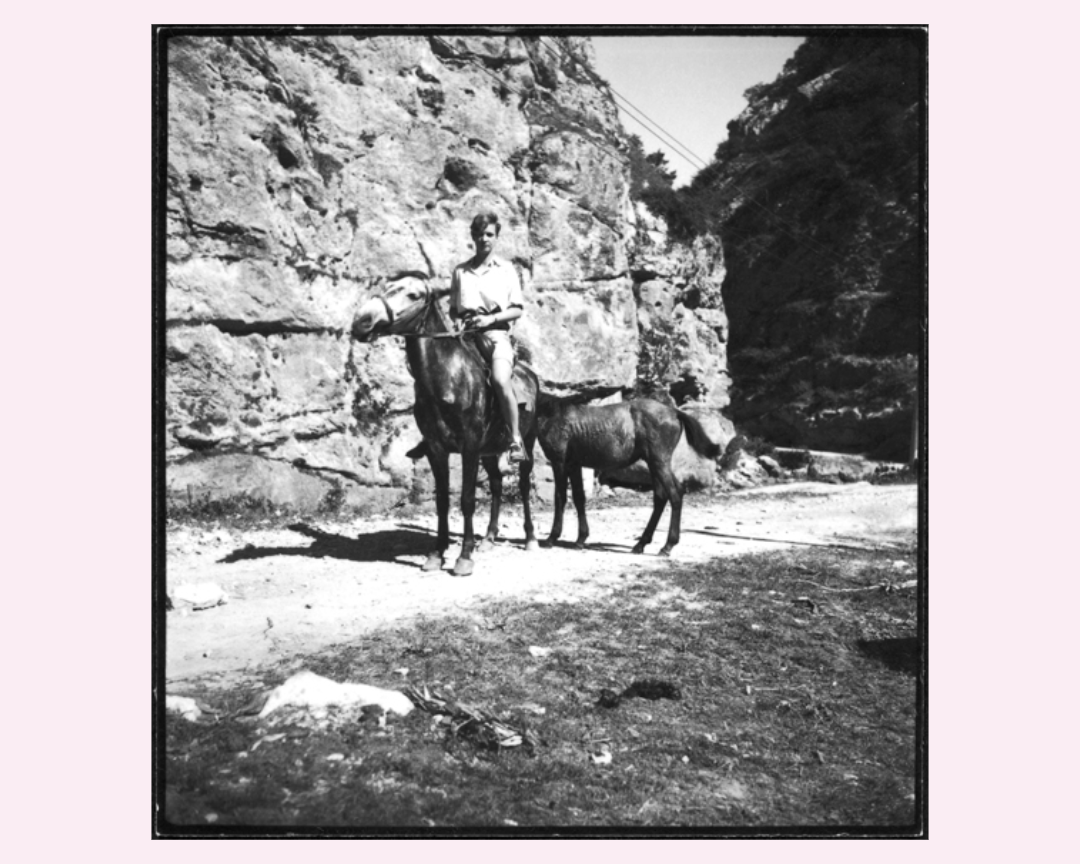

The Shah's soldiers gallop on their dappled horses down the mule track, long whips whirling over their heads, they chase the mares from their resting places, they drive the trembling, stiff-legged foals, they chase the herd along the river to better pasture. In front of the door of the chaikhana stands the innkeeper, enveloped in the blue smoke of his samovar. This valley has become a busy street overnight! A caravan of heavily laden mules comes down the Afjé Pass, the drivers walk behind the animals, stopping at the chaikhana. Nomads are moving up the valley, a large family, a whole clan. Where will they pitch their tents? - The pasture on the valley floor is barren, the Shah's horses have ran across it. The nomads overtake their patient donkeys, striving towards the top of the pass, the children urge the donkeys on, shouting, the women walk upright, on their heads are bundles of lambskin, copper kettles. In their midst walks a camel, it is their only one, it towers over them as if they were carrying an image of a god!

***

I’m still looking: manifold life. The first hour of the morning has begun its course around the globe... Oh, to climb up! To look from the roof of the world, over its mountain edges and cliffs! Down to the blue of the Persian Gulf, which is girded by deserts! The sun is high, it is still summer, heat still trembles over the plain of Tehran, it is still cool in the green gardens of Shimran - there is still time! Desire to follow the roads, the white tracks, the rivers - desire to discover the cities, the oases, the golden domes above palm trees - oh, what insatiable thirst!

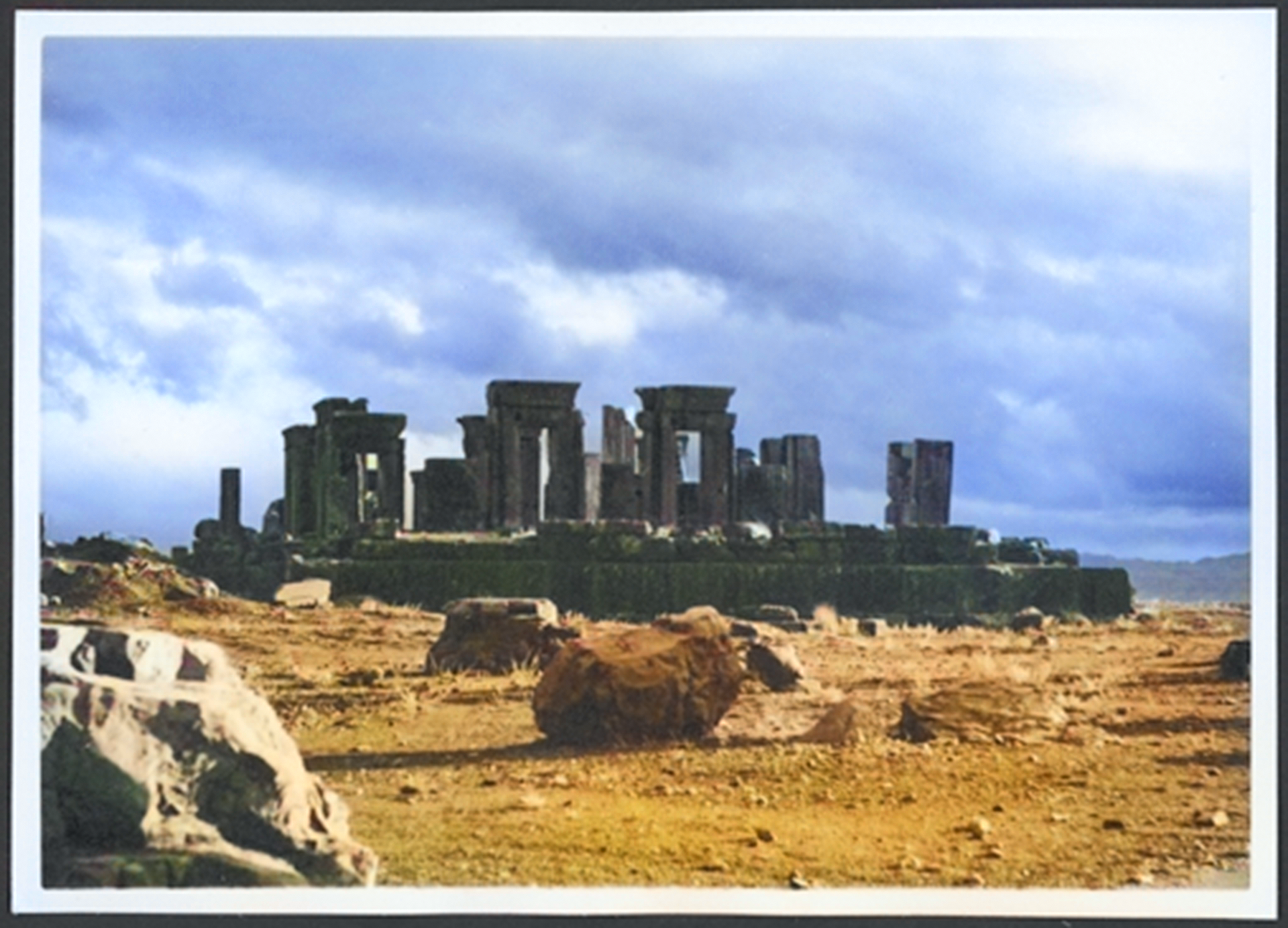

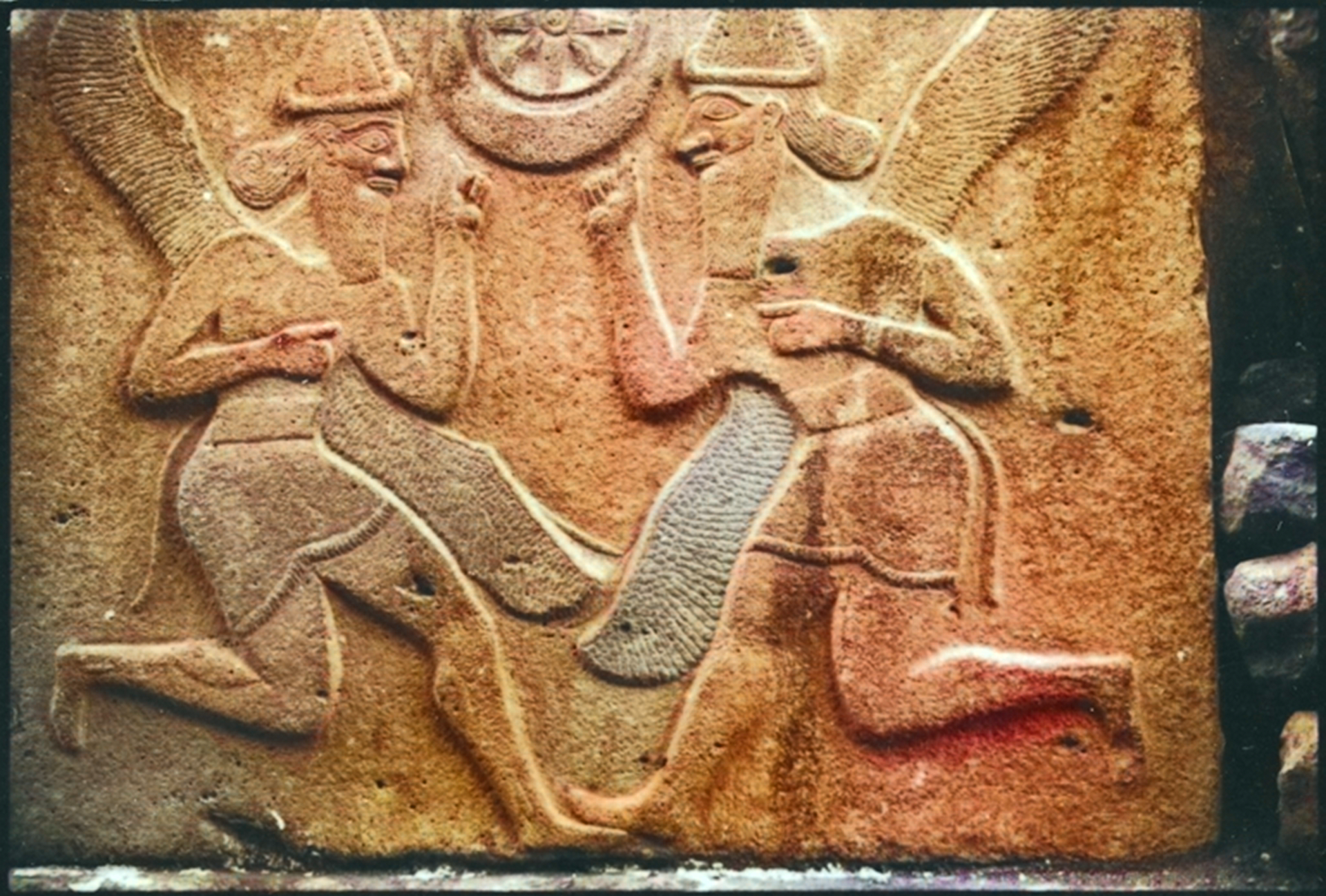

Persepolis: the royal terrace hangs as if on ropes over the plain, the splendor of its stairs, its palace is towered over by slender columns, in the ruins of the mighty hall lies the gigantic bull's head, broken. Perspective over the dusty yellow plain, at the end of which the mountains still rest like stranded ships.

Naksch-i-Rustem, towering rock walls, the house of Zoroastrians, the burial chambers of the kings - tribute bearers, torch bearers, buffalo, lions, dogs, dromedaries and wild boars haunt the gray stone -, on the pinnacle the extinguished fire altars, above that there is only the sky. To see it all once more!- The road to Shiraz shoots through the plain, straight as an arrow, and disappears into distant hills. Beyond the top of the pass there is a blue gate, beyond the gate you descend into the charming town, to the poets' graves, to the cypresses, to the magical gardens. In their shade, by the brightly tiled pond, I lay for a whole day, the cypresses rose up on Florentine hills. To return once more... Magics, a thousand in number, and I tremble: one lifetime will not be enough to remember them all!

Is it true that I stood once on the Meidan-i-Shah, the polo fields of Isfahan? Is it true that I looked once from the "High Gate" onto the city, onto its shining mosques, its bazaar alleys teeming with people, that I once sat in front of a chaikhana, in the shade of the willows, next to turbaned men, nargile smokers, farmers, begging dervishes? - One walked through the crowd, blind, in a tattered silk coat, a tall cap embroidered with Koran motifs on his head, a pumpkin bowl in his hand. Over there, on the other side of the wide, muddy river, in Djulfa, the Armenians went to mass in the evening.

That same evening I stood in a niche of the large bridge, cabs rushed past me, trucks rolled, the hooves of heavily laden donkeys clattered - veiled women had set up their samovars in the neighboring niches, they chatted and laughed non-stop. Camels turned into the shadows of the bridge roof, heading south. Moonlight lay over the torrents. In the darkness a bright, singing boy's voice rose and received an answer from the other bridge. Bright, brittle voices of the Christian children in the mission of Urumiah, a white-bearded Chaldean priest conducted their heart-rending choir. Urumiah, up in the north, in the paradise of Azerbaijan.

There I slept in the schoolroom of the little girls whose parents, Armenians and Chaldeans, were killed by Turks, Persians and Kurds. The Christian women still crowd the mission courtyard in the evenings and draw water - they fear that the city's Muslims may have poisoned their wells like in the years of the great war. They say: "Back then the canals were filled with the blood of our men, it flowed red through the gardens!" - On a beautiful spring day I went out of town with the students - next to the city gate the wheel of a water mill creaked, there the grain that the missionaries harvested from their fields was being ground - across a meadow path we reached the walled orchard; there were cherries, plums, half-ripe apricots and peaches.

Another time we went to the first hills of Kurdistan; the priest in his pith helmet and white coat was fishing with a rod, the boys took off their clothes, threw themselves into the river and caught the fish in flat baskets. Everywhere in the fields, up to the edge of the town, the old watchtowers were falling apart. From the roof of the mission, you could see the white shore, the black-blue, motionless surface of the salt lake, across the belt of gardens - to the north, the delicate outlines of a mountain range, the Caucasus bathed in sun. I saw the gentle vine-covered hills of Georgia, the villages, the oak forests, I saw again the fortress churches of Mtskhet, the churches of Armenia - the fortified courtyards, the Ossetian towers of the dead. I saw Tiflis again, the city of a hundred languages, the bazaar where all the peoples of Asia come together, I went down into the alleys of the old town, which is thrown together on the steep bank, in a bend of the river - I saw saddled horses in one courtyard, in another a sea of camel humps, in a third women knelt and worked on a roll of goat's felt, carpets piled up in dark vaults, it smelled of pepper, of roasted mutton, of rotten melons. When I pressed my face against the wooden bars of a harem fence, I met dark, almond eyes....

Oh, the luminous sadness of summer evenings on the outskirts of foreign cities, where constant departure reigns - camels, herds of donkeys, riders in huge lambskin hats; the brightly tiled gate lets them out, outside the desert begins, they disappear in a cloud of dust... If only I could remember them! The holy cities, Kadimen, Kum, Meshed, their golden domes - the necropolises of Karbala and Nejaf, the fortified cities, the citadels of Ankara, of Aleppo - falcons soared over their battlements -, the port cities, the ruined hills in the Orontes valley. I climbed up over the pale gardens of Damascus in the middle of the night and flew over the Syrian desert, a frozen sea, an extinguished star - we flew eastwards, towards the wall of flames, velvety light flooded over the sand hills, large shadows wandered below us, the black ridges of Bedouin tents were surrounded by a wall of thorn bushes; a man stepped out, looked up at our plane, then turned east and prayed.

But we had already reached the shimmering Euphrates, we jumped over to the murky waters of the Tigris, we circled over Baghdad, the plane tilted sideways, there hung the minarets and golden domes of Kadimein in the morning sky. Magical names, magical sights, a thousand different magics... I have climbed to the top of the Peitak Pass, a gloomy and huge mountain range, the beginning of Persia - the journey was endless over bare plateaus, through barren valleys, countless windings left behind, and the snow piles, which line the road, growing into dirty yellow walls. One could only look ahead. The wind raced over the highest ridges, which stretched out like bridges in all directions into the immeasurable sky.

***

When I try to remember, it seems to me that we spent days and nights wandering through those great wastelands, driven towards sulphur-yellow sunrises that were swallowed up by the black scorched wastes of the heaps and the snow, until only a dim twilight remained. The sun and moon replaced each other and hung pale in the firmament, the road continued ahead of us, between heaven and earth. Was this the way to the Promised Land?

Should I have avoided it, turned back, one day too late?

Had I ventured too far?

- Had an external hand intervened, a coincidence, and thrown me onto these traces of strangeness?

- This terrible twilight, this deadly grandeur!

***

- I had left the shores of the Mediterranean behind, the vineyards and cedars of Lebanon - the last familiar shore exchanged for the desert, now I was on the ancient peoples’ road, on the royal road of the Achaemenids, at the height of the Peitak Pass. Far from familiar consolations, alone.

The strangeness touched me, I no longer recognized myself. What had so much power over me? What power was I at the mercy of? I was at its mercy! Alienated from myself! - But already on the evening of the second day we reached Hamadan. The road led downwards in huge loops, into a snow-covered plain. Ranges of hills interrupted it, soon villages could be distinguished, smoke curled over the flat roofs of the mud huts, snow melted on the slopes, yellow earth, meager patches of meadow became visible, a small river overflowed with milky water, slender willows leaned over its banks. So there was spring in this land!

A light mist, illuminated by slanting rays of sunlight, covered the scene, making it all the more alive... I forgot the desert, the terribly exposed mountain walls, the frightful twilight. I looked ahead, saw Hamadan lying black on the white plain, the streets running around the great hill of ruins that contains the walls of old Egbatan, clad in gold, silver and lapis lazuli, and all of its astonishments- the city was coming closer, one could already make out the houses, caravan yards, mosques, poplars above the roofs. In the yards, donkeys brayed at the top of their lungs.

We were now driving on the plain, overtaking camels that were walking solemnly through the snow, ice in their shaggy hair, bells banging loudly against their flanks. The land was steaming, bathed in the evening light. And whiteness was in the distance, snow on the fields, huts, herds, trees, water, hills and ever new hills, the breathing earth in the distance - the world was given to me again.

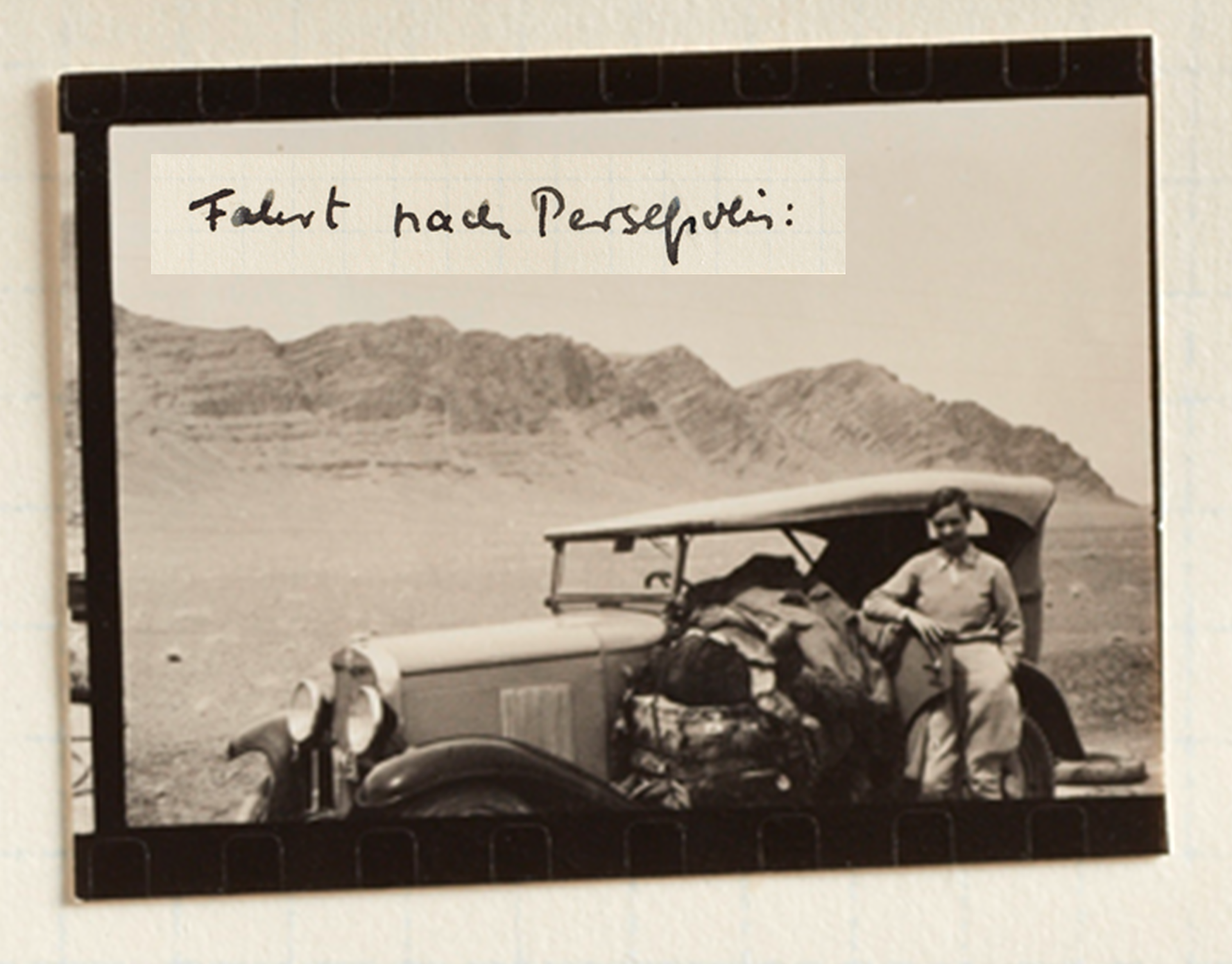

So I entered Persia for the first time.

***

And since then I have tried in every possible way to live in Persia. I have not succeeded. But I have tried!

I left twice, twice returned, as if I owed loyalty to this country! What was I doing here? Had I not seen enough, the first time, did I not know all the mosques of Isfahan by name, had I not crossed the huge plateau, from the gardens of Shiraz to the foot of Elbrus, had I not survived the great mountain paths, waited nights on flooded banks, and at dawn witnessed the birth of the Damavand from the still black land? - It was a different Damavand from the one that blocks the exit to our valley. This one is a giant, an untouchable, unborn son of heaven. Now, in summer, he wears a striped dress made of lava and melting snow. He has a cloud around his shoulders and sometimes covers his light head. He has no feet, he floats over the valleys, towers over all the mountains, greets the sea and marries with the stars. He is mighty and unburdened at the same time. He shines day and night in a gentle light. Without him this valley would be nothing, it would be like a thousand other valleys.

He makes it the valley at the end of the world.

***

Maps are deceptive. They only know one point of view, and in the cross of north, south, east and west the Damavand always remains one and the same. But I have seen a different Damavand. It was, I remember, in the spring, on the stretch between Isfahan and Tehran. In spring, and the streams had overflowed their banks. Streams burst out of mountain gorges, without warning, like avalanches. They rushed into the plain, made their own way, dug their beds, fed on the meager Persian soil, turned yellow and heavy and powerful, as if they wanted to channel their broad floods into a sea. But after just two days, or after just one, they were absorbed by the great plain and left behind only a wasted bed. - Obstacles on the way! - It was my first time in Persia, and I wanted to fly - and was stuck lying on a river bank because there was no bridge, because this river was not planned on the maps, because snow was melting in nameless hills, because it was spring.

In the evening we had set out from Isfahan, my colleague Berger and I. Together with the camel caravans, our car had passed the colorful gate, outside we overtook the caravans, one after the other - the bells rang all along the road. A driver shouted a warning to us, he sat masked on the camel’s, his felt coat pulled over his head. - "What is he shouting?" -

"Slowly, slowly, a big pool is coming..."

Then Berger stepped on the brakes. The road broke off, the earth had burst, a crack gaped, a nighttime stream raged through it. In the middle of the water lay a truck like an animal that had broken its knees. With a lamp that we connected to the battery, we searched for the bank. Up to our hips in the water, we looked for a ford. Nothing but trickling sand under our feet! And the flood almost swept me away! - I felt my way forward, behind me I heard the engine start, the headlights slid over the stream, Berger steered the truck down the embankment, the wheels splashed, were washed over, but the truck moved! - I shouted: "Keep to the right" - then the engine stopped. The wheels had dug themselves into the sand, were spinning idle. I went back. "We'll get it free," shouted Berger, "as long as the magnet doesn't get wet!" - Fighting obstacles, fighting against the water without a bridge, against the sand, against the cold, against the darkness.

Calling to each other, communicating over the roar of the stream. Saving the car, reaching the bank, working together! - We opened the hood and wrapped my scarf around the magnet. We managed to anchor the jack between stones. We pushed our goat’s hair blankets under a wheel and started the engine.

It hissed, it ran - the car leapt forward and sank again. We looked for the blankets, pulled them out of the water, one was torn. Standing on the running board, we caught our breath, lit cigarettes. Then once more... we paved the ford with stones, our arms went numb in the icy water. It was midnight, one o'clock, two o'clock. Finally the bank, smooth, steep. Insurmountable? - Berger was already at the wheel, the engine revved up, the front wheels slid over the edge of the bank, the axle hit the ground. I was still in the water, I held my breath: "We're landing!"

Why do I remember it so clearly and still hold my breath now?

***

The car was up there, on the reclaimed road, the engine still trembling with exhaustion. Berger gave me whiskey to drink, put a dry pustin around my shoulders.

The dawn was getting ready, warm shimmers touched the black plain. It was a desert plain that stretched out before us: dryness, bareness, stone, a handful of earth, prey to the wind - isolated tufts of grass, yellow and lifeless. What a sight! - The eyes get tired of searching for the horizon. - Patience, it will soon be day. Golden streams will flood the desert.

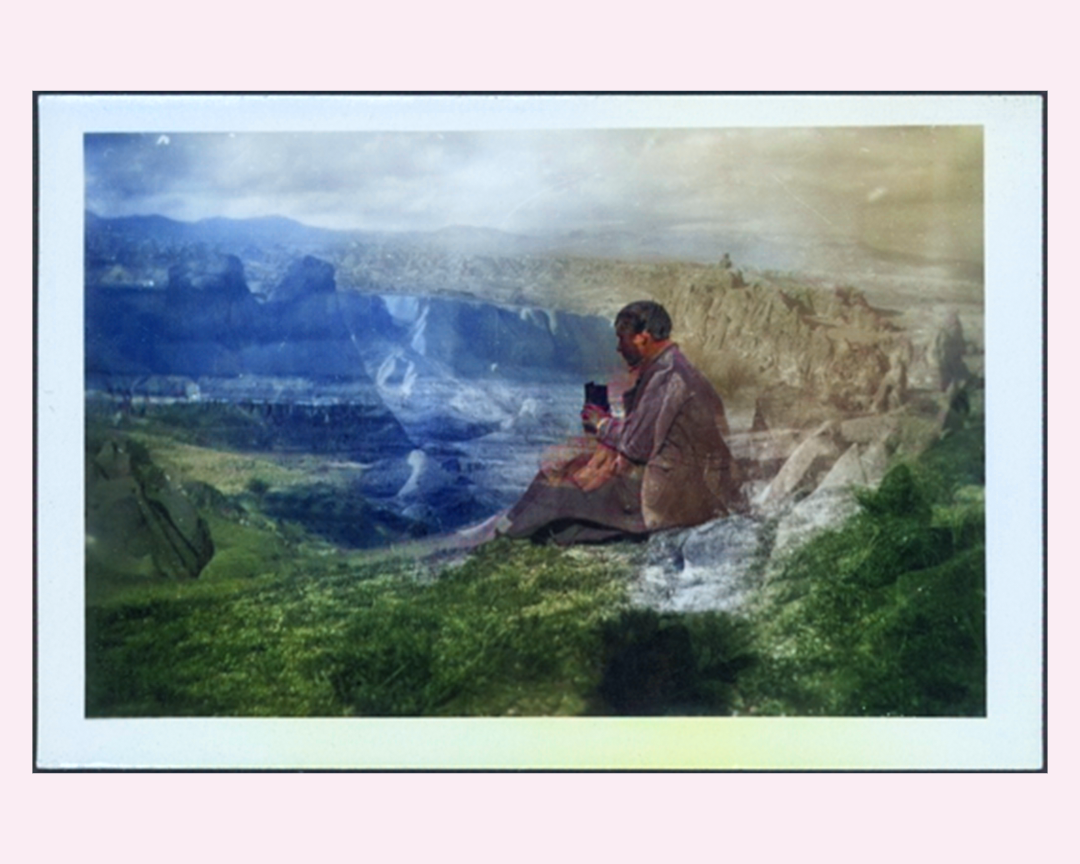

Patience.... Then the Damavand appeared on the outermost edge of the plain. A tiny triangle in the blue night sky, immaculately white, shining - and I saw it for the first time! Berger, as excited as I was, took out his Leika. "It is eighty kilometers away! We must wait for the sun!" he called to me. We waited.

We photographed the Damavand from eighty kilometers away. And the sun warmed us and dried our clothes.

*****

Next: "The Happy Valley" ch. 4