Things I Can't Stop Thinking About

#1: The First Crusade

An overview. With pictures.

12.30.23

*****

At the time of the First Crusade, Muslim societies were flourishing in a wide variety of domains, including medicine, science, and agriculture.

11th C.: Avicenna oversees preparations for the treatment of smallpox

Muslim scholars expanded on Greek, Persian, and Indian medical knowledge. They established some of the earliest hospitals in human history, where physicians contributed significantly to medical research and authored groundbreaking treatises.

The scientific knowledge of Muslim societies during this period can't be overstated. Scholars embraced a wide range of disciplines— from mathematics and astronomy, to geography and optics. Islamic institutions of higher learning integrated many of these disciplines, fostering the exchange of knowledge and contributing to scientific advancements.

Sophisticated agricultural practices allowed these societies to increase water access, and to promote agricultural production in arid regions. Crops as diverse as citrus fruits, watermelon, cucumber, rice, and cotton were cultivated successfully, thanks in part to a depth of scholarly knowledge regarding soil, climate, seasons, and ecology.

9th C.: Botanical manuscript by Abu Hanifa al-Dinawari

These crops would eventually reach Europe, through trade and conquest. In fact, all of these advancements would play a significant role beyond their borders, influencing European developments in these same areas for centuries to come.

***

By comparison, 11th-century Europe was struggling and isolated, suffering through a severe famine.

The famine was interpreted as punishment from God. So were the periodic raids and invasions from Muslim armies, which occasionally reached as far north as France.

"Christian and Saracen armies in battle" (date unknown)

Not much was known about Islam in Medieval Central Europe. The East was imagined as a land of monsters, and of outrageous heresies. Islam itself was described as a polytheistic Christian heresy.

"Saracens, Demons, and Jews": Representations of the East in medieval Central Europe

In his chronicle from 1101, The Deeds of God Through the Franks, Guibert of Nogent paints the Muslim prophet “Mathomus” as a dangerous con-man whose “law” gives “free rein for every kind of shameful behavior”*: polygamy, prostitution, homosexuality, and so on.

In Guibert’s telling, “Mathomus” is punished by God for his hubris; and, after a painful death, he is eaten by flatulent pigs. Later chroniclers embraced and expanded this portrayal, calling Muhammed “a madman and a liar who ‘seduced Arabia’”*, and who preached the total, violent destruction of non-Muslims.

***

In his famous speech at Clermont, in 1095, Pope Urban II inaccurately described the city of Jerusalem as having been usurped from Christians by bands of “Persians”. These “enemies of God”, he said, had overturned the altars and had filled the baptismal fonts with blood. Christians had been forcibly converted, even forcibly castrated, and Christian women raped.

"Pope Urban II Preaching the First Crusade in the Square of Clermont": Francesco Hayez, 1835

The overt goal of the first Crusade was self-evident: to take back this allegedly stolen territory, and to avenge these allegedly harmed Christians. Its secondary goal was to thin out and disperse a starving and restive population, whom the Church leaders and nobility feared would otherwise revolt.

*****

In Medieval conceptions of history, it seemed inevitable that cultural dominance would pass from Eastern regions to the West. They imagined the course of history, like the course of the sun, as beginning in the East, then passing gradually to the civilizations of the West, before ending (soon enough!) in apocalypse.

With that said, according to some Muslim accounts, the first Crusaders initially planned on capturing territories in Africa, not in the Levant. But, at this early stage of their campaign, they lacked sufficient funds and manpower.

The Catalan Atlas (1370s-1380s), with King Mansa Musa of Mali: "The richest man alive".

Roger I of Sicily puts it well, in Ibn al-Athir's chronicle: “As far as we are concerned, Africa is always there. When we are strong enough, we will take it.”**

For the time being, they turned to Jerusalem.

***

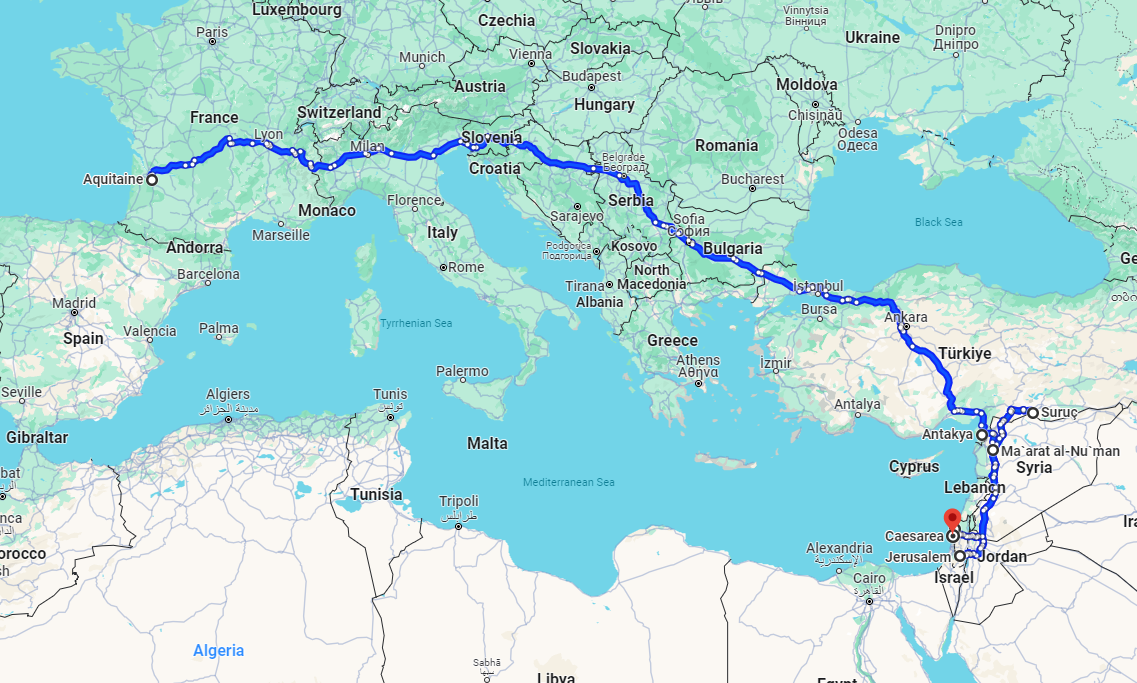

By the way, not until the 13th century would Crusaders call themselves “Crusaders”. During this first Crusade, they called themselves “pilgrims”: armed pilgrims. According to al-Athir, the Emperor of Constantinople would not let these “pilgrims” pass into the Levant unless they promised him the city of Antioch.

The first band of about 500 men reached Antioch in 1097, and put the city under brutal siege for 8 months. When they finally broke through the gates, they sacked the city, and slaughtered the inhabitants.

Siege of Antioch (14th century)

Siege of Antioch (16th century)

Siege of Antioch (12th century)

Duke of Normandy fighting a muslim soldier during the siege of Antioch-- by Jean-Joseph Dassy (1838)

Hearing this news, leaders from Mosul and Syria rallied their troops, and surrounded the Crusaders in Antioch. For twelve days, the Crusaders had nothing to eat. It’s said that the rich ate their horses, and the poor ate carrion.

The soldier and mystic Peter Bartholomew developed a plan.

He promised the troops that, if they found the Holy Lance in the Church of Saint Peter, then God would allow them to leave the city. (If they couldn't find it, then death was certain!) After three days of prayer and repentance, he led them all to a spot in the Church, and began to dig.

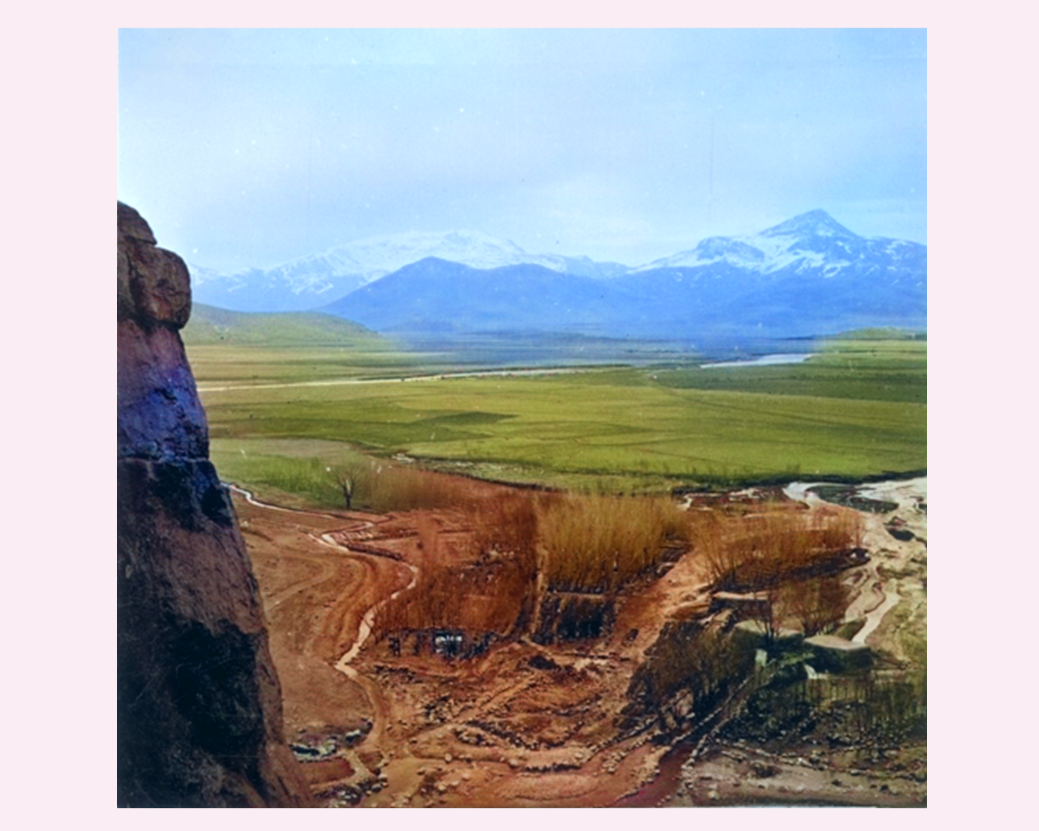

Holy Lance, Antioch (1969, from National Geographic)

Later, Muslim historians would speculate that Bartholomew himself could have buried a lance inside of the Church. In any event, when a lance was discovered, the brigade rejoiced and arranged to leave Antioch the following day.

In fact, they did not have as much trouble as expected: the Turkish emir of Mosul made a severe tactical error in waiting to attack until all of the Crusaders had exited the city. Worse, he had alienated his Syrian allies, who withdrew their troops at the last minute until the only army left standing to fight the Crusaders was from Jerusalem itself. The Crusaders massacred this army, and stripped their camp of arms, food, and horses.

The Road to Jerusalem, Gustave Dore (1877)

Re-equipped, they marched on towards the Holy Land.

***

After leaving Antioch, the Crusaders besieged the city of Ma’arrat al-Nu’man.

"Taking of the fortress of Maarat by the Crusaders", by Henri Decaisne (1843).

They were not expecting how fiercely the inhabitants would defend their city, and for a month they fought them unsuccessfully. When they finally broke through Ma’arrat al-Nu-’man’s defenses, they killed more than 20,000 inhabitants, and took countless more prisoner.

Next they marched to Jerusalem.

But they still wouldn’t have been able to take the city without significant help from the Egyptian army, who brought more than 40 siege engines to aid in the attack. Egyptian forces fought the besieged inhabitants for 6 weeks, until the Crusaders arrived and laid siege to the city for another 6 weeks. They finally broke through Jerusalem’s defenses in 1099. For a week, they pillaged the area, massacring the inhabitants.

"Crusaders Before Jerusalem", Wilhelm von Kaulbach

"The capture of Jerusalem", Jacques de Molay

Undated chromolithograph from a chocolate company: "The capture of Jerusalem"

"Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders", Émile Signol (1847).

They slaughtered tens of thousands of civilians— both Muslim and Jewish— including large numbers of imams and Muslim scholars, many of whom were sheltering in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Then, from the Dome of the Rock, among other holy sites, the Crusaders looted massive quantities of treasure.

Stained glass window depicting the Siege of Jerusalem and Godfrey of Bouillon, in the cathedral of Brussels (1866)

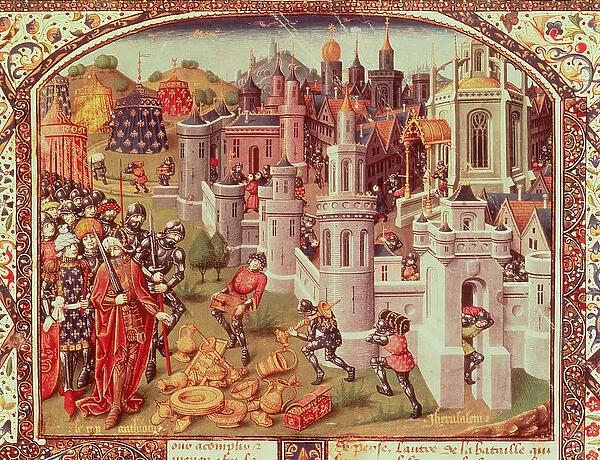

The looting of Jerusalem (15th c.)

*****

Later historians would blame the infighting among Muslim princes for having allowed the Crusaders to overrun the area with such relative ease. Not until 1100 would the Crusaders suffer any serious defeats. Their streak of luck was broken by Prince Kumushtikïn ibn ad-Danishmánd Tailū, who managed to defeat and scatter the Crusader army within a span of a few months. This was followed by another major defeat, when the Crusaders sent another army back to Jerusalem, only to be defeated by armies from Damascus and Hims.

The Crusaders turned instead towards Saruj, in modern-day Turkey.

Besieging the city, they went on to slaughter most of the men, and enslave most of the women. That same year, Crusaders took the port of Haifa and the city of Caesarea.

They murdered or expelled the populations, and sacked the city.

***

Three years later, they attacked the city of Jubail.

The inhabitants surrendered and handed over the city, but the Crusaders broke the peace terms, brutalizing and torturing civilians while seizing the Muslims’ possessions.

***

In 1109, the major city of Tripoli finally fell to Crusaders, who enslaved women and children and sacked the city, looting art, treasures, and the contents of the city’s library.

***

Later that year, the king of Norway, Sigurd I, arrived with more than 60 ships of pilgrims and soldiers. Together with Baldwin I, the new "King of Jerusalem", Sigurd started to make plans for an invasion into the heart of the Muslim empire. To raise funds, they imposed a heavy tax on the conquered cities, reducing entire communities to poverty.

***

In 1110, a group of Sufis, merchants and lawyers from the conquered territories appeared in Baghdad, at the Sultan’s mosque. They smashed the pulpit to pieces; “They wept and groaned… for the men who had died and the women and children who had been sold into slavery. They made such a commotion that people could not offer the obligatory prayers.”** They continued to protest until the Caliph promised that troops would be sent to fight back against the Crusaders.

Still, following their capture, Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and Jerusalem were all made into Crusader States, ruled by a European minority after a feudal model.

With the exception of Iceland and Greenland, these were the West’s first significant colonial venture.

They were not traditional mercantile colonies: they were colonies in the sense that, following the murder and displacement of their populations, they had been repopulated by European settlers, and by Christian communities relocated from elsewhere in the Levant. These states enriched Europe through manufacturing and through trade, effectively granting medieval Europe access to the economies and far-flung trade routes it had, previously, been so isolated from.

The first blow to the Crusader States would not come until 1187, when Saladin recaptured their crown jewel— the city of Jerusalem.

But that thing I can’t stop thinking about will have to wait for another time.

***

*Source: Tolan, John, et al. Europe and the Islamic World: A History. Princeton University Press, 2016.

**Source: Gabrieli, Francesco. Arab Historians of the Crusades. Routledge, 2010.

***Source: Holt, Andrew. “A Colony by Any Other Name: The Latin States of Syria-Palestine.” Apholt, 21 Aug. 2019.

*****

Questions? Comments? Submit them here!