"The Happy Valley" ch. 1

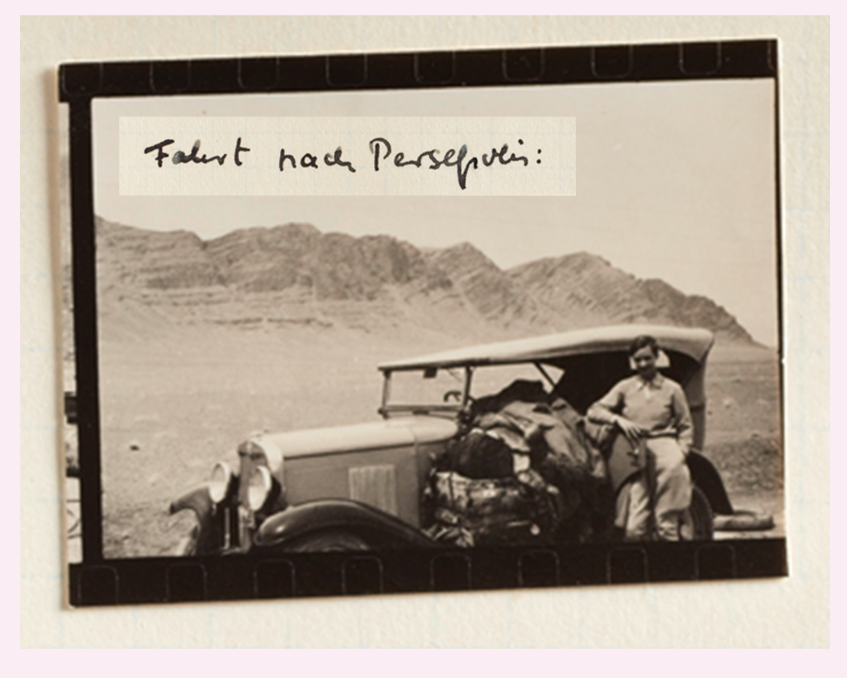

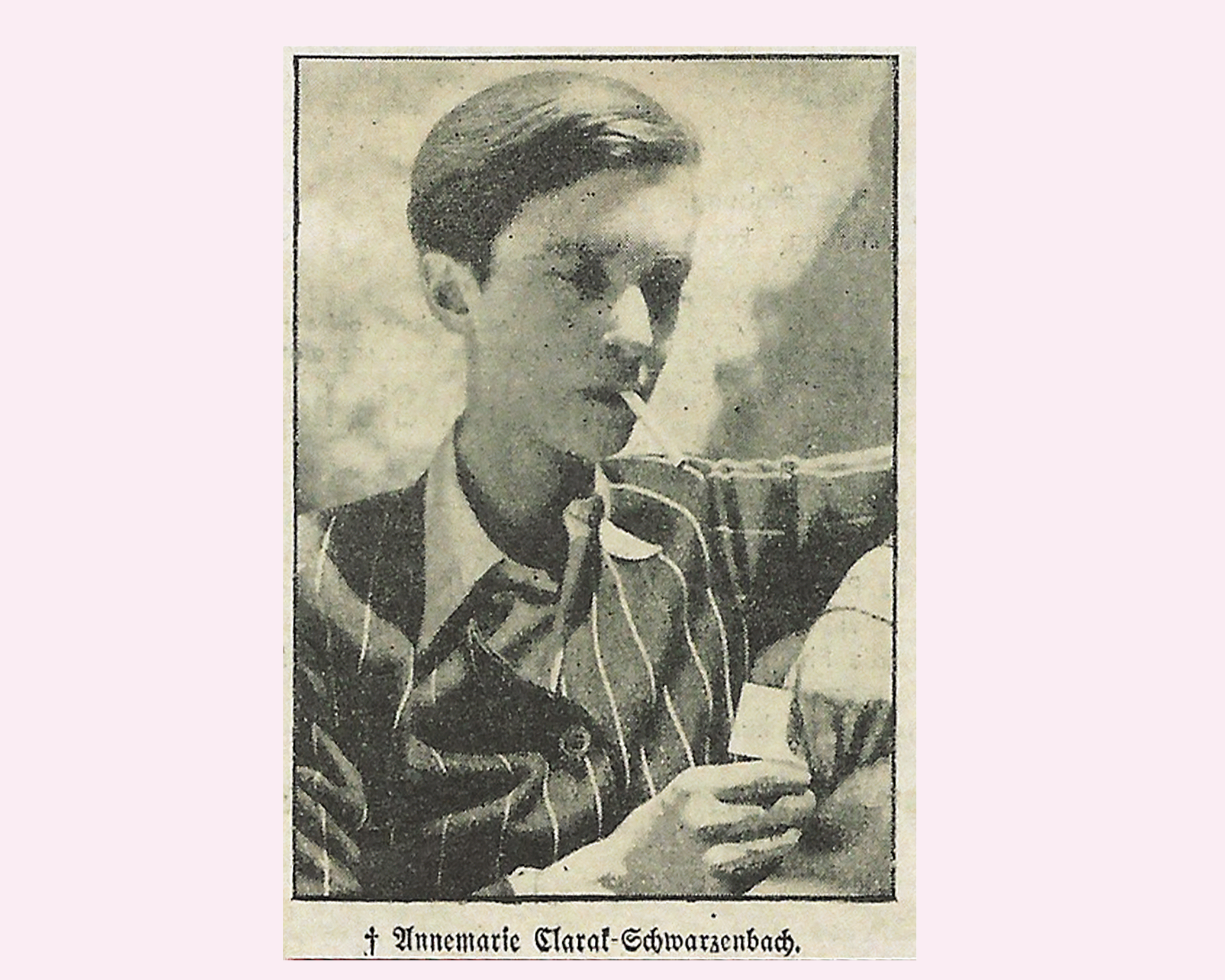

By Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Translated & abridged by Cleo Varra

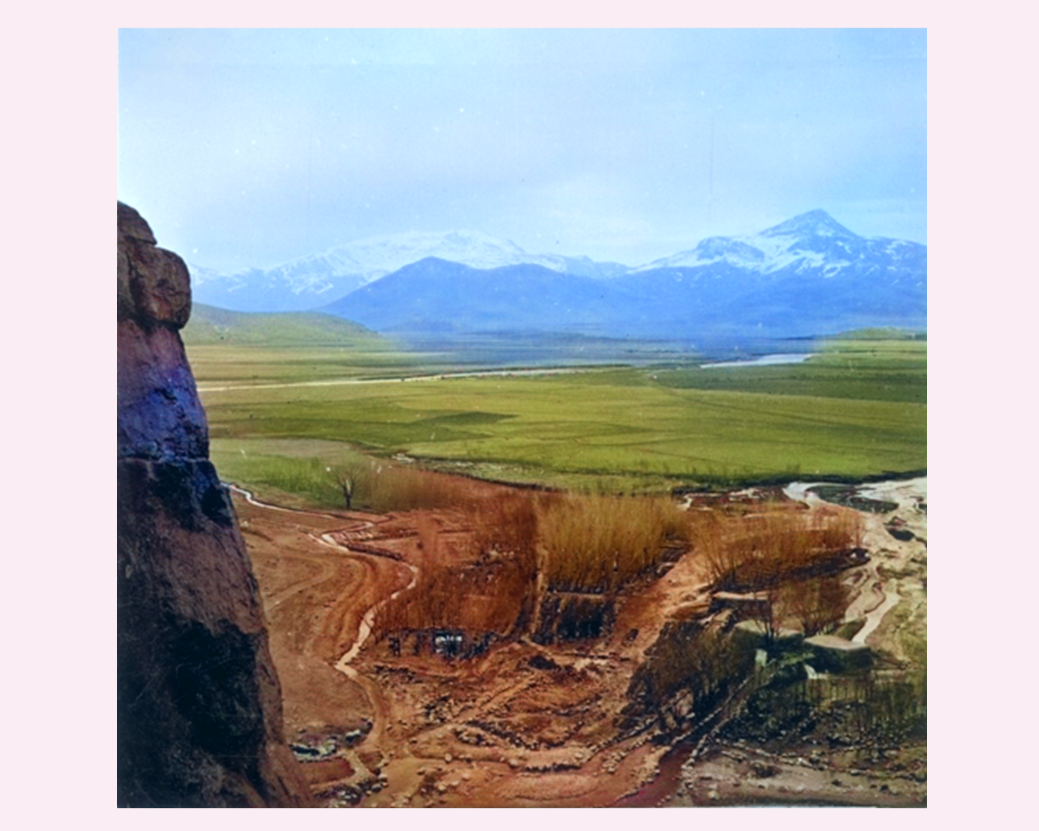

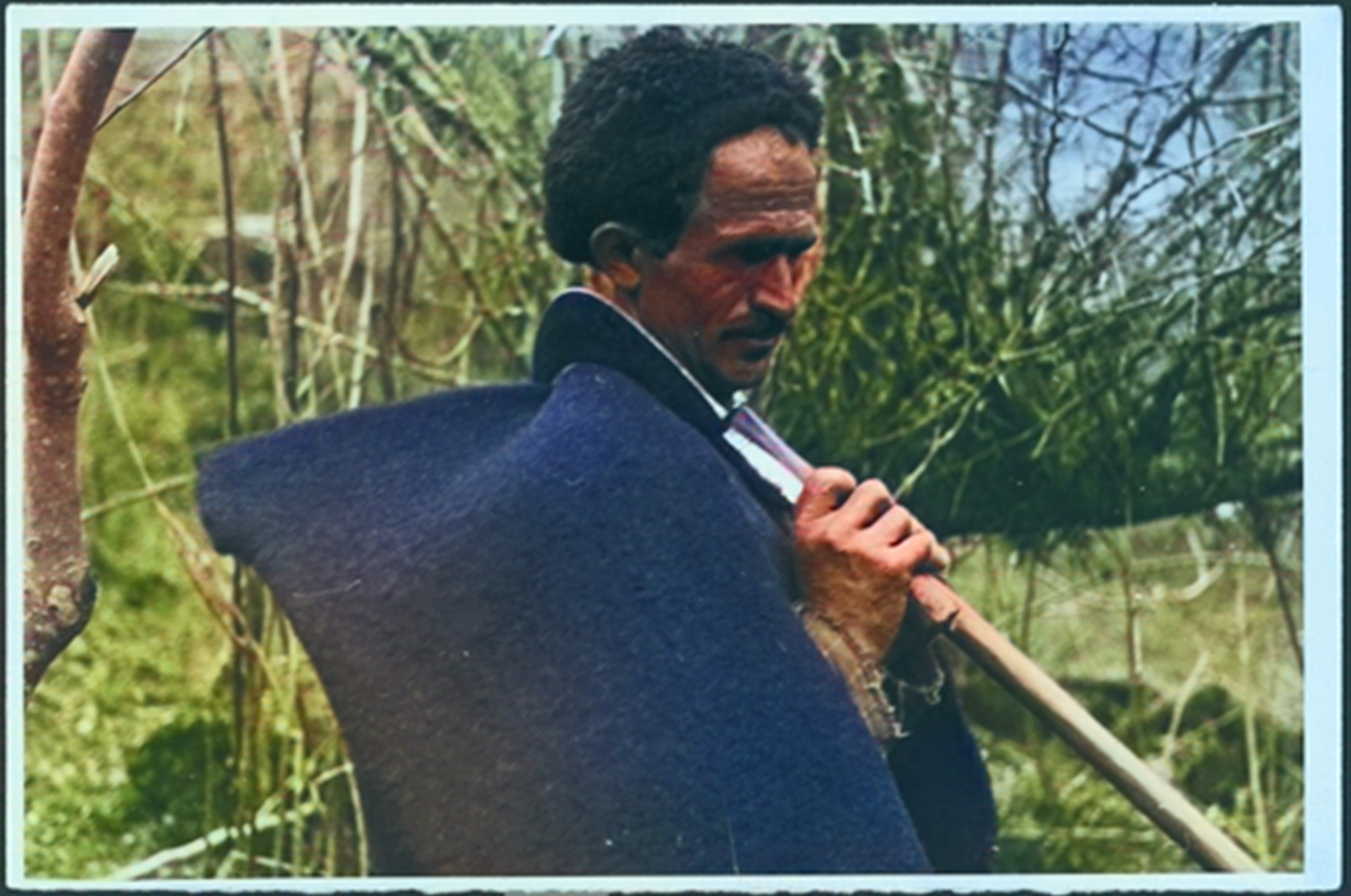

Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Doktor. All photos from the Swiss Literary Archive. Colorized.

Iran- 1935

Our tents are pitched on a grassy bank next to the river Lahr. The valley floor is two thousand five hundred meters above sea level— thirty meters higher than that, if you count from the level of the Caspian Sea, which is much closer to us than the Persian Gulf.

Two thousand five hundred meters - that sounds like a lot, but doesn’t really mean much; because all around us we see chains of mountains that tower mightily over our valley. The hills are gray, and some have steep cliffs of brittle, crazily-broken stones- while others have long sides that gently slope. If you stand in the middle of one of these slopes - and we go up there often to watch the ibexes or just to escape the urge to dully sleep under our tent roofs- you can distinctly hear the incessant trickling of stones.

This monotonous, very faint trickling is the only sound in the wilderness, apart from the roar of an invisible wind that must be blowing over far-away ridges, or even over the hot plain far below, which is separated from our valley by a whole series of nameless passes and mule tracks. I know of no more unbearable sound than the never-ending trickling of the great heaps of stones - indeed, it surpasses even the nightly roar of the caravan bells on the plain, which here I have fortunately escaped.

In summer the caravans spend the hot day in a town or a khan and do not set off until dusk, when the wind is a little cooler. Having lived for several months in a shack separated only by a mud garden wall from the old caravan trail between Tehran and Veramin, I heard the dull roar of bells, the hoarse cries of the drivers and the small, bright tinkling bell on the lead donkey's neck every evening, even in my dreams - but I could never get used to it. Up here I have, so to speak, my undisturbed night's sleep, for camels seldom pass through this valley, and certainly not at night when it is bitterly cold. But there are other noises.

Sometimes I am frightened by the rapid, hurried gurgling of the river water as it winds its way under the banks, stumbling over pebbles - and I think that I can even hear the desperate leaps of trout. Or the wind gets stronger, that terrible high-altitude wind that still carries up here the smell of dust from the burnt plain and tears at the ropes of our tents in darkness. But, as I said, by far the worst thing is the incessant trickling of the great heaps of stones. We should never venture up onto the stones. We do it regardless, again and again.

If you stop for just a moment up there to catch your breath, you first think that you can hear your own rapidly beating heart. But that has already stopped, and what you hear - now clearly, unmistakably - are the trickling heaps of stones. Involuntarily, you look around as if you were expecting help. In the distance, all you can see is a gray and yet strangely mild wasteland.

Below is the river – a narrow ribbon, and the green horse pastures, the white tents, opposite on the other bank is the chaikhana, low, almost hidden in the hollow before the climb of the Afjé Pass, the smoke pours out of the door and winds its way up the silver-gray rock face -, a little further downstream are the nomads' tents, made of black goat's felt, in front of them the women's bright red skirts and their gleaming copper kettles. Everything is as tiny as toys, including the flocks of sheep, and the Shah's grazing horses.

The river disappears behind the Black Cliffs - but there, the Lahr Valley is far from over; do we even know where it leads? Down to Mazandaran, the devil's land on the Caspian Sea, say the nomads. Mazandaran - the sound of that name is wonderful! There, jungle, primeval forest, rice fields, water buffalo on melancholy dunes, humidity, malaria reign supreme. In Gilan, the neighboring province to the west, the rice fields are being drained on the orders of the Shah, and people have come from China to teach the malaria-affected farmers the difficult art of tea cultivation.

The tea from Gilan tastes of straw, the rice from Mazandaran smells of dried manure. The Russian caviar fishermen live in the small coastal towns, in Pehlevi, in Meshed-i-Sehr. In the east begin the steppes, pastures of the Pendin and Teke Turkmen, with their red and camel-brown carpets, their colorful tent stripes and saddlebags. They breed the fastest and most beautiful horses in the East. Their boys, six and eight years old, ride in the great steppe races that take place every autumn. The Russian railway begins in the port of Krasnovodsk, a lonely stretch of rails that run through the steppe: to Merv, to Bukhara, to Samarkand. We are already close to the Tajiks with their curly hair; soon we will be at the Pamir heights, and then on the border of the Heavenly Mountains.

Is your heart beating again?

***

At the mouth of the valley - where we suspect it ends - rises the smooth cone of the giant, unattainable, untouchable pyramid of the Damavand: its body now, in late summer, is striped like that of a zebra. Lava spreads out among the melting snow. But its head is always the radiant white of clouds, and even at night sends out a light, which gently illuminates the sky like the Milky Way. We are used to its magnificent sight - as in this country, we have become accustomed to panoramic perspectives, dust, camel bells, fever, the passing of the hours, morning and evening.

And we see the Damavand wherever we turn: when we leave the tent in the morning, when we wade along the river down to the Black Cliffs, when we go upstream instead and reach the grassy basin where camels graze, goats and fat-tailed sheep. Once I rode to a mound of ruins that lies many hours away in a round valley floor and has not been touched by grave robbers or by any human hand. It is not sought out by the nomads, for not a blade of grass grows on its bare surface, marked by what must have been a thousand years of death. I climbed up, turned my back to the strong wind, and there, in the miraculous distance, the white head of the Damavand rose again.

Today it is shrouded in a light cloud – or is it sulfurous fumes? But the crater has long since died out. Even the Assyrians, who reported that the foreign people of the Medes extended to the foot of Mount Bikni, did not know that it was a volcano. It has been extinguished for three thousand years! Since time immemorial!

As I look across to the Damavand, which has grown so familiar, and which I’m sure I love dearly, because its head touches the sky and its foot is invisible, my heartbeats mingle again with the incessant trickling. I become calmer. Above me the rocky ridges that crown the slopes begin to shine, stripped of all weight, and even if I do not feel light-hearted, the noise that was previously unbearable takes on the quality of a great silence.

***

We sometimes call this valley the "end of the world" because it lies high above the plateaus of the world, far from the well-trodden plain roads; no caravan tracks connect it with the desert and the gates of its necropolises, Karbala and Nejaf, which are teeming with busy people - endless mountain ranges separate it from the sea. One does come across a path here and there, but no one except the nomads know where these paths lead. And it is doubtful whether even the nomads know, although it is they who have trodden the tracks over the centuries.

They say that nomads do not smoke opium. If over in the little chaikhana, where the men sit around the samovar, you think you can smell the sweet smell of opium that brings back memories of the khans of the caravan routes and the teahouses of the cities, you only have to look more closely: on the clay benches by the stove, in the darkest corner, a soldier, one of the Shah's horse-keepers, is squatting, his blouse open, his shoes beside him, smoking. It is better not to look too closely. The innkeeper stands in the way and mutters: "He is ill." That is what he says to us, the faranghi, the foreigners. And all around us there is silence, the men drink their tea through a piece of sugar and do not even turn their heads.

But we should be careful - memories are already starting to wake up.

We should avoid the faces of the opium smokers, and the sweet smells - that of the chaikhana, and that of the wind saturated with dust from the plain, and the hoarse voices of the Persian soldiers, and the warmth that radiates from the samovar, and the smoke from the charcoal that stings the eyes - in short, everything that is alive, everything that was once known, everything that distance evokes.

Distance does not exist, for we cannot climb higher, not high enough to see across our valley and the rocks and slopes of stones that border it.

***

- I used to be free, I used to be able to choose!

Archaeology, travel and adventure, sites on the Alexander routes, the rubble fields of Asia – "Istanbul, Archaeological Institute" – the first address in the distance. Unforgettable hour of departure! – Life stood on the threshold of the sleeping car that took me through the Balkan countries – countries shrouded in twilight, shepherds' mourning on yellow hills… I did not know the meaning of the words "freedom" and "captivity", they could not harm me. There gleamed in the morning light the walls of old Byzantium, the domes of Constantinople, the copper roofs of the Istanbul bazaar, and ships with rust-brown sails sailed on the shining sea: to Cyprus, to Egypt, Greece, to the shores of Arabia….

Archaeology, travel and adventure, sites on the Alexander routes, the rubble fields of Asia – "Istanbul, Archaeological Institute" – the first address in the distance. Unforgettable hour of departure! – Life stood on the threshold of the sleeping car that took me through the Balkan countries – countries shrouded in twilight, shepherds' mourning on yellow hills… I did not know the meaning of the words "freedom" and "captivity", they could not harm me. There gleamed in the morning light the walls of old Byzantium, the domes of Constantinople, the copper roofs of the Istanbul bazaar, and ships with rust-brown sails sailed on the shining sea: to Cyprus, to Egypt, Greece, to the shores of Arabia….

Should I have known where the path of my freedom would lead?- Should I have known? - All the paths I took, all the paths I avoided, ended here, in this valley which has no exit and must therefore resemble the land of the dead.

The darkness is now sinking like a cloud, the rock face shimmers, the river reflects it, and across the way our white tents stand out clearly. I go down to the bank; a foal lies in the deep grass, its delicate hooves crossed. And all around me on the valley floor, from the bank to the rock face, the Shah's horses are sleeping.

*****

Next: "The Happy Valley" ch. 2